Manhattan Psychiatric Center

| Manhattan Psychiatric Center | |

|---|---|

| |

| Established | 1868 |

| Construction Began | 1869 |

| Opened | 13 December 1871 |

| Current Status | Demolished (Kirkbride and original buildings) |

| Building Style | Kirkbride Plan |

| Architect(s) | Alexander Jackson Davis |

| Location | Wards's Island, NY |

| Architecture Style | English Gothic with Mansard roof |

| Alternate Names | New York City Insane Asylum Male Department, Ward's Island Asylum |

[[|300px|left]]

WORK IN PROGRESS 9/29/11

Contents

Background and Origins

Since 1839 the City of New York had been operating an asylum on Blackwell's Island for the care of the cities insane. At the time the vast majority of the insane under municipal care were poor immigrants, which at the time were pouring into New York City. As a result the population of the Blackwell's Island Asylum had steadily risen and was maintained in a perpetual state of overcrowding, providing only custodial care. To combat the rising population the asylum built a three story building for violent patients and later expanded to a three story building, formerly a workshop for the neighboring workhouse. Finally a series of one story pavilions were built however by 1868 the asylum only had accommodation for 640 of the 1035 patients under their care. The lack of room for expansion on Blackwell's Island, already hosting the city Asylum, Prison, Almshouses, and Workhouse, caused the city to look elsewhere. Nearby Ward's Island had been owned by the Department of Emmigration since 1847 and was already home to other city institutions. As a result a site was picked and the new branch of the asylum was established in 1868, opening to patient on December 12, 1871.

History

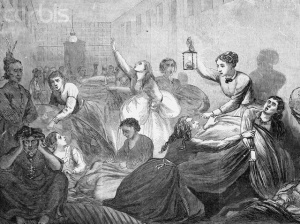

The hospital was visited in the 1840s by both Thomas Story Kirkbride and Charles Dickens, neither of whom were impressed by conditions inside the hospital. After his visit Dickens wrote "...everything had a lounging, listless, madhouse air, which was very painful. The moping idiot, cowering down with long disheveled hair; the gibbering maniac, with his hideous laugh and pointed finger; the vacant eye, the fierce wild face, the gloomy picking of the hands and lips, and munching of the nails: there they were all, without disguise, in naked ugliness and horror." In 1858 there was also fire which destroyed part of the asylum, though it was swiftly rebuilt.

By of 1866 the hospital had grown to several buildings, three of which held patients. These were the Asylum, in the original building, the Lodge or "Mad-house", and the Retreat. The Asylum was housed in the original 1836 structure, consisting for two wings meeting at a right angle, joined in the center by an octagonal tower. Each wing consisted of three stories and an attic. The three primary stories house patient rooms on either side while the attic houses the sick rooms. One wing houses men and the other women. The central octagon was used for physician's apartments, offices, and parlors. This building was partially modeled after the Hanwell Asylum in England.

The Retreat was a three story workshop building formerly used by the workhouse but was used by the Asylum to house female patients as they outnumbered male patients. In the lodge there were 4 halls dedicated to females while only two were for males. The Lodge was where the more violent and newly admitted patients were housed. The new patients were kept here until their disposition could be positively identified. Those where were considered non violent were moved to either the Asylum or the Retreat.

Other buildings as of 1866 consisted of the Cook-house, where patients food was prepared. Also in the cook house was the laundry facilities and the the engine room which provided steam heat to the hospital. There was also a stable, blacksmith shop, carpenter's shop, a paint shop, as well as a dead house. 15-20 Acres under control of the asylum was used for the patients benefit, either in the form of recreational ground or as farm land for their food. Four one story wooden pavilion buildings were also completed by 1868 and used to accommodate 70 female patients each.

Nellie Bly

One of the most famous cases associated with the hospital was the journalism of young female reporter Nellie Bly, who in 1887 entered the hospital under the guise of insanity under assignment from Joseph Pulitzer. She wrote "From the moment I entered the insane ward on the Island, I made no attempt to keep up the assumed role of insanity. I talked and acted just as I do in ordinary life. Yet strange to say, the more sanely I talked and acted, the crazier I was thought to be by all...." Now trapped Bly was tormented with rotted food, cruel attendants, and cramped and diseased conditions. After talking with oter patients she becamse convnced many were as sane as she was, writing

"What, excepting torture, would produce insanity quicker than this treatment? Here is a class of women sent to be cured. I would like the expert physicians who are condemning me for my action, which has proven their ability, to take a perfectly sane and healthy woman, shut her up and make her sit from 6 a.m. until 8 p.m. on straight-back benches, do not allow her to talk or move during these hours, give her no reading and let her know nothing of the world or its doings, give her bad food and harsh treatment, and see how long it will take to make her insane. Two months would make her a mental and physical wreck." She was held in the Asylum for ten days before she was finally released with the help of Pulitzer.

Her report, later published in the book Ten Days in a Mad-House, resulting in not only embarrassment for the Institution but a grand jury investigation into the conditions and how so many "professionals" had been fooled. The end result was an $850,000 increase in the budget of the Department of Public Charities and Corrections as well as their recommendation of changes proposed by Nellie. Ultimately, this report brought about the end of the Asylum Blackwell's Island.

Closing

When the hospital on Ward's Island was completed on December 12, 1871 with accommodations for 500 all male patients from Blackwell's Island were transferred there. Despite this transfer of 400 patients the overcrowding at Blackwell's was so extreme 400 patients still slept on the floor nightly. In 1880 a new branch of the hospital was opened on old buildings on Hart Island and by 1886 new buildings had been begun at Central Islip, on Long Island. By 1892 the New York City Hospital consisted of four departments, The original on Blackwell's Island, a large complex on Ward's Island, Hart's Island, and the new facilities at Central Islip, with a total patient population of 7478 patients.

In 1890 the Federal Government took control of the Emigration Department, and when the new Emigration Station on Ellis Island opened in 1892 the former emigration complex and hospital on Ward's island was left under control of The New York City Asylum. In 1894 the 2000 patients from the Blackwell's Island Asylum were transferred to accommodation's on ward's island, bringing an end to the Asylum on Blackwell's Island.

The Asylum building on Blackwell's was taken over by the Metropolitan Hospital, which modified the buildings for the needs of a medical hospital. The Metropolitan Hospital continued to operate here until 1955 when it moved to Manhattan, leaving the former Asylum abandoned.

Today all that remains of the former Blackwell's Island Asylum in the central octagon tower which made up the center of the original building. After the Metropolitan Hospital left in 1955 the hospital sat vacant and the wings were demolished leaving only the Octagon which was ravaged by fire and neglect. In 1972 it entered the national register of historic places. Luckily the building has been restored when it was incorporated into a new apartment complex built on the ground of the former Hospital.

Images of Blackwell's Island Asylum

Main Image Gallery: Blackwell's Island Asylum

Links

The institutional care of the insane in the United States and Canada, Volume 3