Blackwell's Island Asylum

| Blackwell's Island Asylum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Established | 1834 |

| Construction Began | 1836 |

| Construction Ended | 1841 |

| Opened | 1839 |

| Closed | April 1894 |

| Current Status | Demolished |

| Building Style | Pre-1854 Plans |

| Architect(s) | Alexander Jackson Davis |

| Location | Blackwell's Island, NY |

| Architecture Style | Tuscan |

| Alternate Names |

|

Contents

Background and Origins

The Blackwell's island Asylum was the first lunatic asylum for the city of New York and the first municipal mental hospital in the country. The institution was the first in what later became a larger system of New York City Asylums which was comprised of hospitals on Blackwell's, Ward's, and more briefly Hart's and Randall's Islands in New York City.

The Blackwell's Island Asylum was part of a larger complex of city buildings on the island, including at one point or another a Prison. By the early 1800's New York City had become the largest urban area in the United States, a population heavily bolstered by immigration and industrialization. As a result there were large numbers of indigent insane, whose care fell to the city. In the years leading up to 1825 the city's insane were either kept in the city almshouse or at the Bloomingdale Asylum. It was in the year 1825 that the insane of the city were moved to the basement and first floor of a building built as a General Hospital on Blackwell's Island, part of a larger complex of municipal institutions on the island comprising of an almshouse and prison. It was here where the mentally ill remained in conditions described by the very commissioners in charge of the hospital as "a miserable refuge for their trial, undeserving of the name Asylum, in these enlightened days". It was not until 14 years later, in 1834, that the city approved the construction of a separate institution for the insane on the island as a result of long communications from Dr. James McDonald. However the hospital was not completed until 1839.

History

This new institution, located on the northernmost end of the island, was at this time completely separated from the other institutions on the island and given autonomy. Despite this new autonomy and purpose built hospital the conditions at the hospital quickly degraded and for the duration of its existence the hospital was plagued by overcrowding, under-funding, and scandals. In 1840 only one year after opening the population stood at 278, while by 1870, with no significant improvement in housing or infrastructure, the hospital housed 1,300, far more than any state hospital at the time. This overcrowding served to greatly hinder not only living conditions at the hospital but also impeded efficient internal administration. The inability to properly administer a facility of this size was made apparent by the substandard diet of the patients, frequent outbreaks of disease, and even the employment of convicts from the Blackwell's Island Prison as attendants to reduce costs.

This large patient population was a result of the hospital's general use to provide cheap custodial care to insane immigrants, with a population of 534 immigrant patients compared to only 121 native born patients in 1850. When considering the population of New York City at the time was less than half immigrant the true disproportion of this statistic is made apparent. The superintendent during the 1850's recognizing this appealed to the state for financial aid, citing both the extreme burden placed on the city by having to care for non-resident insane and the fact citizens of New York City were forced to pay taxes to support the State Asylum at Utica, which provided them no aid. His suggestions that the state either open an asylum in the city or take on the responsibility of immigrant insane fell on deaf ears and the population of the hospital continued to grow, by 1868 the hospital had accommodations for 640, but faced a population of 1035, necessitating the creation of a new city asylum on Wards Island in 1871.

The hospital was visited in the 1840s by both Thomas Story Kirkbride and Charles Dickens, neither of whom were impressed by conditions inside the hospital. After his visit Dickens wrote "...everything had a lounging, listless, madhouse air, which was very painful. The moping idiot, cowering down with long disheveled hair; the gibbering maniac, with his hideous laugh and pointed finger; the vacant eye, the fierce wild face, the gloomy picking of the hands and lips, and munching of the nails: there they were all, without disguise, in naked ugliness and horror." In 1858 there was also fire which destroyed part of the asylum, though it was swiftly rebuilt.

By of 1866 the hospital had grown to several buildings, three of which held patients. These were the Asylum, in the original building, the Lodge or "Mad-house", and the Retreat. The Asylum was housed in the original 1836 structure, consisting for two wings meeting at a right angle, joined in the center by an octagonal tower. Each wing consisted of three stories and an attic. The three primary stories housed patient rooms on either side while the attic housed the sick rooms. One wing housed men and the other women. The central octagon was used for physician's apartments, offices, and parlors. This building was partially modeled after the Hanwell Asylum in England.

The Retreat was a three story workshop building formerly used by the workhouse but was used by the Asylum to house female patients who outnumbered male patients. In the lodge there were four halls dedicated to females while only two were for males. The Lodge was where the more violent and newly admitted patients were housed. The new patients were kept here until their disposition could be positively identified. Those considered non-violent were moved to either the Asylum or the Retreat.

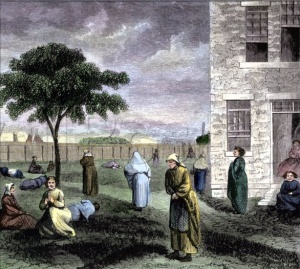

Other buildings as of 1866 included the Cook-house, where patient meals were prepared. Also in the cook house were the laundry facilities and the engine room which provided steam heat to the hospital. There was also a stable, blacksmith shop, carpenter's shop, a paint shop, and a dead house. 15-20 Acres under control of the asylum were used for the patient's benefit, either in the form of recreational ground or as farm land for their food. Four one story wooden pavilion buildings were also completed by 1868 and used to accommodate 70 female patients each.

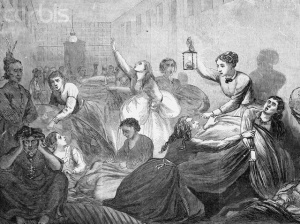

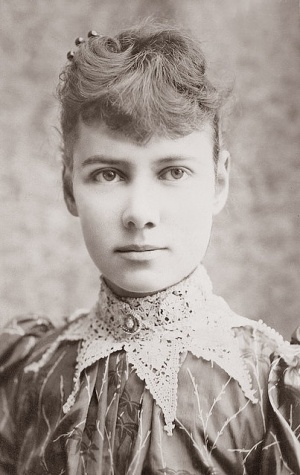

Nellie Bly

One of the most famous cases associated with the hospital was the journalism of young female reporter Nellie Bly, who in 1887 entered the hospital under the guise of insanity under assignment from Joseph Pulitzer. She wrote, "From the moment I entered the insane ward on the Island, I made no attempt to keep up the assumed role of insanity. I talked and acted just as I do in ordinary life. Yet strange to say, the more sanely I talked and acted, the crazier I was thought to be by all...." Now trapped, Bly was tormented with rotted food, cruel attendants, and cramped and diseased conditions. After talking with other patients she became convinced many were as sane as she was, writing

"What, excepting torture, would produce insanity quicker than this treatment? Here is a class of women sent to be cured. I would like the expert physicians who are condemning me for my action, which has proven their ability, to take a perfectly sane and healthy woman, shut her up and make her sit from 6 a.m. until 8 p.m. on straight-back benches, do not allow her to talk or move during these hours, give her no reading and let her know nothing of the world or its doings, give her bad food and harsh treatment, and see how long it will take to make her insane. Two months would make her a mental and physical wreck." She was held in the Asylum for ten days before she was finally released with the help of Pulitzer.

Her report, later published in the book Ten Days in a Mad-House, resulted in not only embarrassment for the Institution but a grand jury investigation into the conditions and the question of how so many "professionals" had been fooled. The end result was a $1,000,000 increase in the budget of the Department of Public Charities and Corrections as well as their recommendation of changes proposed by Nellie. Ultimately, this report brought about the end of the Asylum Blackwell's Island.

Closing

When the hospital on Ward's Island was completed on December 12, 1871 with accommodations for 500, all male patients from Blackwell's Island were transferred there. Despite this transfer of 400 patients the overcrowding at Blackwell's was so extreme 400 patients still slept on the floor nightly. In 1880 a new branch of the hospital was opened in old buildings on Hart Island and by 1886 construction of new buildings had begun at Central Islip, Long Island. By 1892 the New York City Hospital consisted of four departments: The original on Blackwell's Island, a large complex on Ward's Island, Hart's Island, and the new facilities at Central Islip, with a total patient population of 7478.

In 1890 the Federal Government took control of the Emigration Department, and when the new Immigration Station on Ellis Island opened in 1892 the former emigration complex and hospital on Ward's island was left under control of The New York City Asylum. In 1894 the state took control of the NYC Asylum system under lease, with one of the stipulations being the closure of the Asylums on Hart's and Blackwell's Island within five years. This same year many patients from the Blackwell's Island Asylum were transferred to accommodations formerly belonging to the New York City Homeopathic Hospital on Ward's Island. Transfers continued to former Emigration Hospital buildings on Ward's Island as well as the new colony at Central Islip on long Island. In February of 1901 the final patients were transferred to the newly finished buildings at Central Islip, bringing an end to the Asylum on Blackwell's Island.

The Asylum building on Blackwell's was taken over by the Metropolitan Hospital, which modified the buildings for the needs of a medical hospital. The Metropolitan Hospital continued to operate there until 1955 when it moved to Manhattan, leaving the former Asylum abandoned.

Today all that remains of the former Blackwell's Island Asylum is the central octagon tower which made up the center of the original building. After the Metropolitan Hospital left in 1955 the hospital sat vacant and the wings were demolished leaving only the Octagon which was ravaged by fire and neglect. In 1972 it entered the national register of historic places. Luckily the building was restored when it was incorporated into a new apartment complex built on the ground of the former Hospital.

Books

Damnation Island: Poor, Sick, Mad, and Criminal in 19th-Century New York, By: Stacey Horn ISBN - 9781616205768

Images of Blackwell's Island Asylum

Main Image Gallery: Blackwell's Island Asylum

Links

The institutional care of the insane in the United States and Canada, Volume 3