Rhode Island State Hospital

| Howard State Hospital | |

|---|---|

| |

| Established | 1868 |

| Opened | 1870 |

| Current Status | Active |

| Building Style | Cottage Plan |

| Location | Cranston, RI |

| Architecture Style | Georgian Revival |

| Peak Patient Population | 3,300 (est.) in 1955 |

| Alternate Names |

|

History

Eighteen frame buildings were constructed in 1870, and that November 118 mental patients were admitted - 65 charity cases from Butler Asylum, 25 from town poor houses and 28 from asylums in Vermont and Massachusetts where the state had sent them. The patients at the State Asylum were poor and believed beyond help, as is reflected in the evolution of names for the asylum. Initially it was to be called the State Insane Asylum; in 1869 the Asylum for the Pauper Insane; and in 1870 the State Asylum for the Incurable Insane. In 1885, to relieve the cities and towns from the burden of supporting their insane poor, the General Assembly adopted a resolution that the State Asylum for the Insane should serve as a receiving hospital for all types of mental disorder, acute as well as chronic, thereby merging the two. By giving over the Asylum to “undesirable” elements, the poor, the incurable, and the foreign born, the upper and middle classes thus restricted their own ability to use it. Therapy was second to custody.

In 1888, the General Assembly appropriated funds for a new almshouse to replace the frame building that had been originally built for the insane. Known now as the Center Building, the Almshouse was also designed by Stone, Carpenter and Wilson. Its name acknowledges the prevailing trend in institutional design, as evidenced in the House of Correction and State Prison, as well: the installation of a large central administration building with office and residential facilities for the staff and public eating and worship spaces for the inmates who were segregated in wings flanking the central structure. In this case, the wings housed 150 men and 150 women and includes an additional wing, the children’s “cottage” for sixty children. Opened in 1890, the three-and a half story stone building stands as a series of long buildings running north-south and interrupted regularly by octagonal stair towers. Its handsome stone work and red-brick trim and its site behind copper beach trees on a bluff overlooking Pontiac Avenue make the Center Building one of the most visually striking structures in Rhode Island.

1900s

The major improvement of the decade before the turn of the century was the appointment of Howard’s first full-time medical superintendent, Dr. George F. Keene, which signaled the introduction of professionally trained, therapy-oriented administrators at the State Farm. The new orientation manifested itself in the building plan for the Hospital for the Insane created in 1900 from designs by the prominent Providence architectural firm of Martin and Hall. Based on the contemporary practice of constructing hospitals for the insane on the cottage or ward plan, “thereby establishing small communities in separate buildings that are more easily taken care of and administered,” the plan was the first at Howard to establish a campus-like quadrangle arrangement of buildings in place of one large self-contained structure.

A key part of the new plan was a communal dining room, modeled after the one in the hospital at Danvers, Massachusetts. As a result of Martin and Hall’s recommendations, the Service Building was constructed in 1903 and included a dining room measuring 195 feet by 104 feet, which could seat 1,400 people.The master plan outlined by Martin and Hall was slow in being realized. In 1912, the Reception Hospital (A Building) was opened. With 184 beds it was intended to permit appropriate diagnosis and classification of patients as they entered the institution. This effort became a reality with the assignment in 1916 of psychiatric social workers to the state hospital.

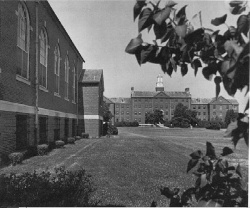

The Training School for Nurses was opened in conjunction with the Reception Building, and when the Rhode Island Medical Society held its annual meeting there, it recorded its approval. Nonetheless, the new facility did not relieve overcrowding, and in 1913, 2000 people were sleeping on the floor at the State Hospital for the Insane. The completion of B Ward in 1916 and C Ward in 1918 responded to the population increase and at last fulfilled Martin and Hall’s plan for “simple and dignified” buildings and “plain red brick walls with pitched roofs, without any attempt at ornamentation.” Standing just west of Howard Avenue and opposite the old House of Correction, the Martin and Hall quadrangle signals the beginning of a new mode of construction at Howard - red brick buildings in a simple Colonial Revival style grouped around a quadrangle and containing dormitories, single rooms, and porches as well as treatment facilities.

The concern for professionalism at the staff level soon affected the administration as well. In 1918, the General Assembly unified the Board of State Charities with the Board of Control and Supply, which controlled state expenditure and formed the Penal and Charitable Commission. Until this time there had been considerable tension between the two Boards, the Board of Supply frequently imposing fiscal restraints on the Board of State Charities’ efforts at reform. Although some proposed plans to relieve overcrowding were postponed due to shortages caused by the First World War, the new Commission constructed a new building for the criminally insane and additional dormitories.

The old twelve foot high solid fence which shut off patients from the outside world was replaced in 1919 by a lower lattice one with a view of the surrounding countryside. This change alone symbolized the change in attitude which was articulated in the 1920 Annual Report:

“The commission tries to save dollars, but it would rather save a man or a woman. It wants to see the plants in Cranston, Providence, and Exeter a credit to Rhode Island, standing like so many Temples of Reform, Education, and Philanthropy. But it is even more desirable that its work should be represented in reconstructed Living Temples in the morals, minds and bodies of those who have been ministered to by these public administrators. For it is better to minister than administer.”

These efforts at reform in the treatment of the insane were paralleled by a new attitude towards the infirm. The Almshouse became the State Infirmary and attention was focused on the medical, not the social, disabilities of the inmates.

Expansion

It was the infusion of large amounts of federal Works Progress Administration (WPA) funds that dramatically altered the appearance of the Howard complex and permitted, if briefly, appropriate physical accommodation for patients, inmates, and attendants. Overcrowding has been a chronic problem at Howard and only the large-scale construction program of the WPA could solve it. Despite the building effort of the 1920s, in 1933 the State Hospital, with accommodations for 1,550, housed 2,235 and was labeled the most overcrowded mental hospital in the northeast.

In the years 1935-1938 twenty-five buildings were erected for the State Hospital for Mental Disease, three for the State Infirmary, and three for the Sockanosset School. The appearance of Howard was dramatically altered by this construction which went up so fast the Providence Journal declared a “new skyline rises at Howard.”

Built in a uniform, red-brick, Georgian Revival style, the structures comprising the State Hospital and State Infirmary are grouped in campus fashion on either side of Howard Avenue. Among the most interesting are the Benjamin Rush Building, with an ogee gable inspired by the Joseph Brown House in Providence, and the cluster of Physician’s Cottages which finally permitted the hospital staff improved residential accommodations. Taken in total, the buildings constructed at Howard by the WPA incorporated a uniformity of style, scale, material, and siting that is striking. Historically they represent the coming together of national policy and local initiative. Architecturally, they present one of the most lucid statements of the Georgian Revival in Rhode Island.

But despite the tremendous improvement made possible by the WPA, by 1947 conditions at Howard had once again deteriorated due to overcrowding. The Hospital for the Insane, built for 2,700 beds, held over 3,000 patients. Increased salaries were approved to help recruit additional staff, and it was proposed that a master plan be developed. In 1947, the “Hospital Survey and Construction Act of Rhode Island,” stemming from the federal Hospital Survey and Construction Act of that year, was passed. Through it, the governor was authorized to appoint an advisory hospital council to advise and consult with the Department of Health in implementing the Survey and Construction Act. However, no immediate action was taken, and in 1949 the population at Howard reached its highest in history without significant new construction. Interestingly, in 1959 an expert from Boston declared that the conditions at Howard were shameful and yet “relatively good” compared with mental hospitals in the country. The problem stemmed not from a lack in the annual budget (Rhode Island ranked twelfth nationwide in the amount spent per patient) but in the inability to raise capital funds to match federal programs.

In 1962, the General Hospital and State Hospital for Mental Diseases merged to become the Rhode Island Medical Center. The former became the Center General Hospital and the latter the Institute of Mental Health. In so doing, Rhode Island was the first state to create therapy units for its mentally ill, an approach pioneered at the Center General Hospital. As a result, four buildings housing elderly patients were transferred to the jurisdiction of the Cranston General Hospital in order to remove the stigma of residing in a mental hospital.

In 1967, the Medical Center was divided. The Center General Hospital was designated to serve as an infirmary for the prison and the Institute of Mental Health. Both hospitals are administered by a new Department of Mental Health, Retardation, and Hospitals, In 1977, the IMH was divided into nine units to deal with specific categories and regions of patients. The institution is currently undergoing another philosophical re-orientation, encouraging group homes away from the environment of Howard. The extent of this change will very likely depend on federal support, but if carried out extensively, it will help to redefine the role of Howard just as previous changes in attitude have.