Bayview Hospital and Asylum

| Bayview Hospital and Asylum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Established | 1773 |

| Current Status | Active |

| Building Style | Single Building |

| Location | Baltimore, Maryland |

| Alternate Names |

|

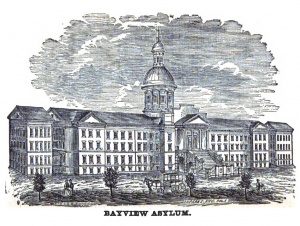

The following is from the 1866 book "The stranger in Baltimore": The Bay View Asylum, a new institution for the paupers of the city, is the first prominent object that strikes the eve of the traveler as he approaches the city on the Philadelphia Uailroad. The building is exceedingly imposing in appearance, and situated upon a hill high enough to render it conspicuous for many miles. Some $500,000 have been expended on the premises, and every rare and modern appliance afforded to render the Asylum and its grounds equal to the best in the world. The wings and centre building give an aggregate front of 714 feet, whilst it is three stories in height, including the basement. It is built of Baltimore brick of excellent quality, and, when completed, will have a massive entrance of granite with a roof and entablature supported by four large fluted columns, which will present an imposing Appearance, and give an air of completeness and solidity to the whole. One striking feature of the interior is the main hall of the principal story, which extends the entire length of the structure, is of unusual height, and supplied with tessellated marble flooring. This hall, as well as those above it, 'Communicate by spacious doorways to nearly all the principal rooms, and thereby contributes much to the ventilation, a very i-desirable feature in so large a building. Ample space has been . jxeserved for the accommodation of the officers and others 'i engaged in the house. The centre hall, which crosses the building, is well lighted, and contains the stairways which conduct both below and above. To the right of the hall is a spacious rApartment in which the Board of Trustees transact their business, whilst opposite is what is styled the reception parlor, . about 50 feet square.

The principal and most important feature in the building is the admirable manner in which it is heated and ventilated. 'There are four horizontal return-flue boilers, each 30 feet long .-•and 4 feet in diameter, set in massive brick work, supported by iiron guilders from the top. Only two boilers are necessarily rused at the same time, whilst all are located on the north side of the centre building, and beyond the laundry and kitchen; all of which are separate and distinct from the main building; From the boilers run large main steam pipes, which diverge in every direction, and supply the numerous coils placed in the halls and rooms. The construction of the coils used is different from the old style, being vertical, with substantial and handsome manifold bases for the bottom and return heads for the top. The temperature of every room is easily controlled by the engineer. The condensed steam from each coil is returned to the engine for use in the boilers. The ventilation is produced by the stack, which measures in the clear 13 feet in diameter, and is 125 feet high. The ventilating Hues from the entire building connect with this stack, the air in the same being rarified by the heat from the boiler stacks. The plumbing has been done in the best manner, all the piping being galvanized wrought iron, which is proof against gnawing irits. The laundry arrangements are of the most perfect character, steam, of course, being the great agent used. One twelve-horse power engine propels the machinery, and an independent boiler is provided for summer use, when.the large boilers are not wanting.

The principal arrangement for ventilation is a large stack of brick, the foundation of which is on a ltvel with the superstructure, while the top ascends above the roof, thereby passing a continual current of air. The top of the cupola rises to the height of 184 feet, whilst the base is estimated at ln7 feet above tide-water. From the top a magnificent panoramic view of scenery is presented, including the harbor, bay and river, the. fortifications and the entire city. The superintending architect of the building was John W. Hogg, Esq. More than seven millions of brick have been used in the work of erection.

The grounds consist of forty-six acres, which were purchased of the Canton Company at the rate of $150 per acre. and they will be kept in the highest style of cultivation, the better class of inmates doing the work as far as possible. There are now in the wards 716, and the general health is reported unusually good.

The principal management of fitting it up for occupation, was performed by W. W. MaughIin, James McDougal, William Callow, A. W. Poulson and James F. Ross, E.<qs., trustees appointed by the Mayor, whose labors, though gratuitous, were of the utmost advantage to the city in point of economy and completeness. Water is conveyed from Mount Royal Reservoir, a distance of five and a half miles, at an expense for pipes, &c.t of over $65,000. Permits tor visitors must be .obtained from the Trustees.[1]

Contents

History

Bayview began life in 1773 as the Baltimore City and County Alms House. Situated on what is now Baltimore’s east side, near where Maryland General Hospital is today, it was repeatedly pushed to the fringes of urban development. It landed on its present site, a rolling parcel of land far to the southeast of the city and overlooking the Chesapeake Bay, in 1866 when it came to be known as Bay View Asylum. It housed the poor and insane and was known as a dreaded, sinister place. Bay View was a name Baltimore mothers evoked when they disciplined their children, as in, “If you don’t behave, you’re going to wind up at Bay View!”

The link with Johns Hopkins was forged in the mid-1880s, even before its hospital opened, when William Welch, University pathologist, began studying Bay View Asylum patients in his research. Later, medical students from Hopkins joined University of Maryland students doing clinical rotations there.

In 1925 Bay View Asylum was renamed Baltimore City Hospitals—plural because it encompassed three separate hospitals: one for acute care, another for chronic care, and a third for tuberculosis patients. Psychiatric patients continued on at City Hospitals up through the 1930s when they were admitted to state institutions.

In the 1950s, City Hospitals was bursting at the seams with patients. Beds in its long, open wards were spaced about 10 feet apart and separated by curtains. It was now a teaching venue exclusively for Hopkins medical students, as Maryland had pulled out of its City Hospitals arrangement. Programs Bayview would become famous for, such as gerontology under Nathan Shock and later Mason Lord, were thriving. The National Institute on Aging’s Gerontology Research Center opened in 1968, the same year that community support from the Kiwanis’ Club established the now renowned Baltimore Regional Burn Center.

Cities throughout the United States were struggling in the 1970s and 1980s to maintain their municipal hospitals, and Baltimore was no exception. Run by municipal bureaucrats who knew little about hospital administration, City Hospitals was on the brink of financial disaster.

A bright light was Chesapeake Physicians, one of the first faculty practice plans in the country. When it was established in 1972, revenue for physicians and medical staff began flowing in. And yet, by 1980, Baltimore Mayor William Donald Schaefer was exploring bids from for-profit health care companies to take over City Hospitals, which was losing millions annually. Meanwhile, Chester Schmidt, president of Chesapeake Physicians, and Philip Zieve, chief of medicine, were lobbying The Johns Hopkins Hospital to acquire their besieged, but still promising, institution.

In fact, City Hospitals had what Hopkins wanted: Chesapeake Physicians, the region’s only burn unit, kidney dialysis and transplant programs, a long-term care facility, a couple of federal research centers, hundreds of teaching beds—not to mention 134 acres of land. Fearing competition from a for-profit hospital, Robert Heyssel, then president of Hopkins Hospital, and Richard Ross, dean of the medical school, reasoned that the acquisition might make sense—if Hopkins could manage City Hospitals successfully for a trial period and reduce its deficits.

In 1982, under a contract with the city, Hopkins assumed management of City Hospitals and sent a trio of young hospital administrators out to run it. Ronald Peterson, William Ward and Kenneth Grabill dramatically reduced City Hospital’s multimillion-dollar deficits. In 1983, University and Hospital trustees voted unanimously to start negotiations to take over City Hospitals.

Negotiating the deal with Schaefer, Heyssel played hardball. Under the terms of the agreement, the city promised to pay Hopkins $5.4 million over the next four years to cover part of the $8.4 million needed for improvements. Hopkins would loan the remaining $3 million to the city. The city and Hopkins would split profits from developing City Hospitals’ land over the next 20 years. Remarkably, if Hopkins could not operate City Hospitals successfully after five years, it could give it back.

In the end, Hopkins never put a dime of its own into the deal. (It was able to cover its portion of the upgrade expenses with revenue generated at City Hospitals.) Negotiations were concluded in March 1984; the transfer of ownership was effective July 1. City Hospitals was renamed the Francis Scott Key Medical Center, with Peterson its president. Soon thereafter, he added Judy Reitz to the management team.

Today the Bayview Medical Center is a 700-bed community teaching hospital with federal research institutes, nationally known programs and regional centers. Its impact on southeast Baltimore City and County is immeasurable. Its nationally known geriatrics program provides hundreds of elderly people with residential and outpatient care. It houses Maryland’s only burn center, an area-wide trauma center, comprehensive substance abuse programs, a digestive diseases/motility center, and regional centers for neonatal intensive care and sleep disorders.

In the 20 years since the takeover, admissions, surgical procedures and clinic visits have risen consistently. Approximately 2,000 employees have been added to the payroll. Buildings and grounds have been transformed. The campus now is modern and vibrant. Most significantly, considering Hopkins’ worries as it hammered out the City Hospitals deal, Bayview has been in the black.[2]

Images of Bayview Hospital and Asylum

Main Image Gallery: Bayview Hospital and Asylum

Links & Additional Information

References

- ↑ http://books.google.com/books?id=iE0Wjayjsz8C&pg=PA114&lpg=PA114&dq=bay+view+asylum+baltimore&source=bl&ots=cQ9HE8jLkz&sig=jngHu6w2snZGQXZmdSv2y3I_bxM&hl=en&ei=jRsnTeD3JIGBlAeX2unfAQ&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=5&ved=0CDoQ6AEwBA#v=onepage&q=bay%20view%20asylum%20baltimore&f=false

- ↑ http://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/dome/0404/centerpiece.cfm