Difference between revisions of "Institute of the Pennsylvania Hospital"

HerbiePocket (talk | contribs) |

L-Leichtman (talk | contribs) (→Links & Additional Information) |

||

| (3 intermediate revisions by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

There is a tremendous amount of confusion about the [[Pennsylvania Hospital]] in Philadelphia, PA. This is because there were in fact two separate facilities bearing the name. The first, founded in 1751 by Dr. Thomas Bond and Benjamin Franklin was located on Eighth and Pine Streets, and was completed in 1755. This facility is still operational, albeit not for its original purpose. The original structure of Pennsylvnia Hospital is now largely is maintained because of its historic value to the city and state (the modern Pennsylvania Hospital sits behind this building). This original facility found itself overwhelmed by the number of 'lunatic' patients, and regularly had their insane wards overcapacity. The Board of Managers voted to build a second hospital, in what was then rural West Philadelphia, as was the style of such institutions at the time. This second hospital was known as the Institute of the Pennsylvania Hospital, as to draw distinction from their primary facility. This was also the hospital that Dr. [[Thomas Story Kirkbride]] was Superintendent, who is regarded as one of the fathers of American Psychiatry. Both facilities were run under the same Board of Mangers during their tenure, but only one had a specific specialization in behavioral healthcare. | There is a tremendous amount of confusion about the [[Pennsylvania Hospital]] in Philadelphia, PA. This is because there were in fact two separate facilities bearing the name. The first, founded in 1751 by Dr. Thomas Bond and Benjamin Franklin was located on Eighth and Pine Streets, and was completed in 1755. This facility is still operational, albeit not for its original purpose. The original structure of Pennsylvnia Hospital is now largely is maintained because of its historic value to the city and state (the modern Pennsylvania Hospital sits behind this building). This original facility found itself overwhelmed by the number of 'lunatic' patients, and regularly had their insane wards overcapacity. The Board of Managers voted to build a second hospital, in what was then rural West Philadelphia, as was the style of such institutions at the time. This second hospital was known as the Institute of the Pennsylvania Hospital, as to draw distinction from their primary facility. This was also the hospital that Dr. [[Thomas Story Kirkbride]] was Superintendent, who is regarded as one of the fathers of American Psychiatry. Both facilities were run under the same Board of Mangers during their tenure, but only one had a specific specialization in behavioral healthcare. | ||

| − | == History == | + | == Campus History == |

=== Overcrowding at Pennsylvania Hospital: 1817-1834 === | === Overcrowding at Pennsylvania Hospital: 1817-1834 === | ||

| Line 98: | Line 98: | ||

<blockquote>"''during the entire year, the institution has been rather more than comfortably filled, the average number for the whole period, as shown above, being 229, while 220 is regarded as the capacity of the building. Anxious to receive all who desired admission, we have at no previous time refused any suitable applicant; but during a part of the year just closed, we were for a time compelled, although with great reluctance, to decline receiving patients, except under the most urgent circumstances.''"</blockquote> | <blockquote>"''during the entire year, the institution has been rather more than comfortably filled, the average number for the whole period, as shown above, being 229, while 220 is regarded as the capacity of the building. Anxious to receive all who desired admission, we have at no previous time refused any suitable applicant; but during a part of the year just closed, we were for a time compelled, although with great reluctance, to decline receiving patients, except under the most urgent circumstances.''"</blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[File:1180Females.jpeg|250px|thumb|right|Department for Females, circa 1880]] | ||

By May 1854, Dr. Kirkbride had convinced the Hospital’s Board of Managers of the need to build a second, larger hospital building on the West Philadelphia grounds, and to separate the patients by sex, which was the custom of the era. The Managers authorized a $250,000 fundraising campaign and published an "Appeal to the Citizens of Pennsylvania for Means to Provide Additional Accommodations for the Insane." By the spring of 1856 the campaign had raised $209,000 in gifts and private pledges. In March of that year, the Managers authorized the design and construction of a separate building to house, the "Department for Males", and it appointed a building committee to oversee the work. The committee selected Samuel Sloan as its primary architect. Sloan took due consideration of Dr. Kirkbride's suggestions, as well as the guidelines of his predecessor in the Department for Females. Construction began in July, and in October the Managers conducted a ceremony in West Philadelphia in which the Mayor of Philadelphia, Richard Vaux, laid the hospital cornerstone. The new building opened three years later, in October 1859, with a separate entrance on 49th Street, midway between Haverford Avenue and the West Chester Road (renamed Market Street). The new building’s total cost was $322,542.86, but additional expenses– a boundary wall, carriage house, carpenter shop, brought the total expenditure to approximately $350,000.17. | By May 1854, Dr. Kirkbride had convinced the Hospital’s Board of Managers of the need to build a second, larger hospital building on the West Philadelphia grounds, and to separate the patients by sex, which was the custom of the era. The Managers authorized a $250,000 fundraising campaign and published an "Appeal to the Citizens of Pennsylvania for Means to Provide Additional Accommodations for the Insane." By the spring of 1856 the campaign had raised $209,000 in gifts and private pledges. In March of that year, the Managers authorized the design and construction of a separate building to house, the "Department for Males", and it appointed a building committee to oversee the work. The committee selected Samuel Sloan as its primary architect. Sloan took due consideration of Dr. Kirkbride's suggestions, as well as the guidelines of his predecessor in the Department for Females. Construction began in July, and in October the Managers conducted a ceremony in West Philadelphia in which the Mayor of Philadelphia, Richard Vaux, laid the hospital cornerstone. The new building opened three years later, in October 1859, with a separate entrance on 49th Street, midway between Haverford Avenue and the West Chester Road (renamed Market Street). The new building’s total cost was $322,542.86, but additional expenses– a boundary wall, carriage house, carpenter shop, brought the total expenditure to approximately $350,000.17. | ||

The new 'Department for Males' was magnificent, with "a handsome Doric portico of granite in front, and is surmounted by a dome of good proportions. The lantern on the dome is 119 feet from the pavement below, and from it is a beautiful panoramic view of the fertile and highly improved surrounding country, the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers, and the city of Philadelphia, with its many prominent objects of interest." In 1860, the original building, now the "Department for Females," was extensively renovated, and placed in the same condition as the new building. The capacity of the Department for the Insane was thereby doubled, from 220 patients to 470 total. It was now an extraordinary large institution, one of the first to be designed and organized in accordance with the 1851 guidelines of the [[American Psychiatric Association]] (guidelines which had been authored by Kirkbride himself), but it was also was one with critics. Dr. Meigs, in his 1876 history of the Pennsylvania Hospital, acknowledged many of the problems, but defended the hospital, stating: | The new 'Department for Males' was magnificent, with "a handsome Doric portico of granite in front, and is surmounted by a dome of good proportions. The lantern on the dome is 119 feet from the pavement below, and from it is a beautiful panoramic view of the fertile and highly improved surrounding country, the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers, and the city of Philadelphia, with its many prominent objects of interest." In 1860, the original building, now the "Department for Females," was extensively renovated, and placed in the same condition as the new building. The capacity of the Department for the Insane was thereby doubled, from 220 patients to 470 total. It was now an extraordinary large institution, one of the first to be designed and organized in accordance with the 1851 guidelines of the [[American Psychiatric Association]] (guidelines which had been authored by Kirkbride himself), but it was also was one with critics. Dr. Meigs, in his 1876 history of the Pennsylvania Hospital, acknowledged many of the problems, but defended the hospital, stating: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote>''"Occasionally, an outcry has been raised against what the objectors have been pleased to call ‘palaces for the insane.’ What would these critics have? A building to contain from 200 to 250 patients, with officers, attendants, cooks, bakers; with offices, sitting-rooms, bed-rooms, bath-rooms, water-closets, ironing-rooms, and kitchens; can such a building be other than large and imposing? Is it a palace, simply because it is vast? This element of size cannot be avoided, and the question reduces itself to the simple alternative, shall the so-called palace be imposing by the hugeness of its deformity, or by fitness for its purposes, and by the beauty of its outlines? | ||

| + | |||

| + | But such cavils against insane hospitals come only from the thoughtless. I have always felt, and shall always feel, grateful to the Managers of this Hospital, for the fine taste they have shown in the style and architecture of these buildings. Amongst the pious uses of money is the embellishment of cities. | ||

| + | |||

| + | We cannot be too thankful that the buildings for the insane were made handsome, striking, and picturesque. Some one of these cavillers, or any one of us, may yet have to place in an insane asylum some one near and dear to us. Who knows what the morrow shall bring forth? If it were to be so, should we choose a building with the air of a prison, penitentiary, or great uncouth and rambling hotel, or a well-proportioned, attractive, and imposing house for the poor afflicted one to dwell in? No, for one, I rejoice in these handsome and attractive buildings for the insane. I think it must be only a weak, pitiful mind, and a cruel soul, that would refuse to these afflicted ones such sweet pleasures of the senses as we may be able to give them."''</blockquote> | ||

Despite the critics, expensive improvements in the physical plant continued for several years. In 1868, 1873, 1880, 1888, and 1893, five new buildings were constructed for women patients and called the South Fisher Ward, the North Fisher Ward, the Mary Shields Wards, the Cottage House or Villa, and the I.V. Williamson Wards, respectively. In 1864 the women’s "Gymnastic Hall" was funded and constructed and in 1890 a gymnasium was also constructed for the men's campus. At the close of the 19th century the facilities of the hospital for the Insane rivaled those of any similar institution in the nation. | Despite the critics, expensive improvements in the physical plant continued for several years. In 1868, 1873, 1880, 1888, and 1893, five new buildings were constructed for women patients and called the South Fisher Ward, the North Fisher Ward, the Mary Shields Wards, the Cottage House or Villa, and the I.V. Williamson Wards, respectively. In 1864 the women’s "Gymnastic Hall" was funded and constructed and in 1890 a gymnasium was also constructed for the men's campus. At the close of the 19th century the facilities of the hospital for the Insane rivaled those of any similar institution in the nation. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Likewise, the staffing of the 'Hospital for the Insane' steadily expanded through the 19th century and well into the early 20th. A broadly useful view of the hospital may be obtained from the decennial U.S. census returns. In 1850, Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane housed 251 resident patients, and 85 resident staff; in 1860, 276 patients, and 119 staff; in 1870, 327 patients, and 167 staff; in 1880, 376 patients and 218 staff; in 1900, 437 patients, and 267 staff; and in 1910, 446 patients and 291 staff. A community that totaled 336 persons in 1850 more than doubled in size to one that totaled 737 in 1910. In addition to its rapid growth, it was noted for being an extremely self-contained community. There were the officers– the superintendent, the stewards, the matrons, the physicians– and those who cared directly for the patients, such as: the attendants (later called nurses); but even as early as 1850 there were also farm laborers, cooks, men to attend to the fireplaces which heated each room, carpenters, coachmen, and gate keepers, all of them resident staff, living on the grounds of the hospital proper. The number of work specializations increased with each decade, until, in 1910, there were also gardeners, waitresses, laundresses, cleaners, seamstresses, even a masseur, a pharmacist, a buyer of clothing, a bookkeeper, a storekeeper, an engineer, and two messengers. The Department was a neighborhood unto itself. It should also be noted that throughout this period, while the patients were almost all native born, the majority of the staff were natives of Ireland. If these arrangements seemed acceptable in the 19th century, they certainly were challenged by the changing ethnic demographics of West Philadelphia in the 20th century. | ||

=== Turn of the Century: 1883 to 1911 === | === Turn of the Century: 1883 to 1911 === | ||

| Line 111: | Line 121: | ||

The Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane flourished under Kirkbride until his death on December 16, 1883, though for decades after his death, Philadelphia natives colloquially referred to the hospital as "Kirkbride's." Dr. [[John Chapin]], the former Superintendent of the [[Willard State Hospital]] in New York, assumed the role of Superintendent of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane after Kirkbride's demise, following a lengthy election by the Board of Managers. The Board had spent ten months making their selection, which was precarious because of the fame and reputation of Kirkbride. Chapin officially assumed this role on September 1, 1884, and held that office until the resignation from his duties in 1911. He was directly succeeded by Dr. Owen Copp, who initiated a School of Nursing for Men at the Hospital. Dr. Chapin appoints Leroy Craig as the first director of 'the Pennsylvania Hospital School of Nursing for Men'. Craig gains notoriety as the first male superintendent of a male nursing school in the country. Similar schools had previously been established locally at [[Friends Hospital]] and [[Norristown State Hospital]]. The new school of nursing was devoted to training male nurses in generalized nursing practices, as well as the specialization in the disciplines of psychiatric care. | The Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane flourished under Kirkbride until his death on December 16, 1883, though for decades after his death, Philadelphia natives colloquially referred to the hospital as "Kirkbride's." Dr. [[John Chapin]], the former Superintendent of the [[Willard State Hospital]] in New York, assumed the role of Superintendent of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane after Kirkbride's demise, following a lengthy election by the Board of Managers. The Board had spent ten months making their selection, which was precarious because of the fame and reputation of Kirkbride. Chapin officially assumed this role on September 1, 1884, and held that office until the resignation from his duties in 1911. He was directly succeeded by Dr. Owen Copp, who initiated a School of Nursing for Men at the Hospital. Dr. Chapin appoints Leroy Craig as the first director of 'the Pennsylvania Hospital School of Nursing for Men'. Craig gains notoriety as the first male superintendent of a male nursing school in the country. Similar schools had previously been established locally at [[Friends Hospital]] and [[Norristown State Hospital]]. The new school of nursing was devoted to training male nurses in generalized nursing practices, as well as the specialization in the disciplines of psychiatric care. | ||

| − | It is during the second part of the hospital's history that the particulars of its operations change dramatically. Starting in 1876 the number of patients admitted to the inpatient began to drop, which was credited to rise of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania's involvement in psychiatry as a matter of the public health. This rise in psychiatric care was found to be startling in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. When Kirkbride opened the new asylum in 1840 there were a total of 275 beds available for those who suffered from mental illnesses. shared by the facility and [[Friends Hospital]]. By 1895, 7,000 inpatient beds had been created between various: private and state hospitals, as well as local sanitariums. While this trend would continue well into the 20th century, Pennsylvania Hospital's inpatient population maximum would not change from the five-hundred beds it was allotted following its expansion in 1853. While the Institute would remain an industry leader, it was longer the only psychiatric facility available to the public regionally. | + | It is during the second part of the hospital's history that the particulars of its operations change dramatically. Starting in 1876 the number of patients admitted to the inpatient based upon charity began to drop, which was credited to rise of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania's involvement in psychiatry as a matter of the public health. This rise in psychiatric care was found to be startling in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. When Kirkbride opened the new asylum in 1840 there were a total of 275 beds available for those who suffered from mental illnesses. shared by the facility and [[Friends Hospital]]. By 1895, 7,000 inpatient beds had been created between various: private and state hospitals, as well as local sanitariums. While this trend would continue well into the 20th century, Pennsylvania Hospital's inpatient population maximum would not change from the five-hundred beds it was allotted following its expansion in 1853. While the Institute would remain an industry leader, it was longer the only psychiatric facility available to the public regionally. |

| + | |||

| + | In contrast to many state facilities, the physical site and grounds of the 'Hospital for the Insane' were indeed "of the first class" status, and would remain so in public opinion. So too was the number of staff attending, and the staff’s general care of their patients. AS the 19th century progressed, it became clear that the 'Hospital for the Insane' was increasingly becoming an elite institution. West Philadelphia, however, was growing up all around the Hospital and between 1886 and 1891 the Managers of the [[Pennsylvania Hospital]] took four actions which demonstrated the extent of the city’s presence. The first was perhaps the most significant. In May 1886, the Contributors to the Pennsylvania Hospital authorized the Managers "to purchase such area of land, within a reasonable distance from the city, not exceeding 500 acres, in order to prepare a site for such future adjuncts or additions to their Hospital as may hereafter be required or found desirable." In June of that year, the Managers formed a committee which began buying land in Newtown Square, Delaware County. By May 1891, five years later, the purchases totaled "607 acres". The land was designated for the future of the 'Hospital for the Insane', and in 1892 the Managers announced tentative plans for building on the acreage. However, this would never materialize. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Then, in 1888 and 1889, the Board of Managers clashed with the City of Philadelphia over their charity status and the issue of medical exemption from city taxation. In the summer of 1887, the Board of Managers authorized the construction of the "Cottage House" or "Villa" for female patients at the hospital. The new structure opened in June 1888 to mild fan fair. The municipal government made a claim against the hospital for water supply to the new building, justifying its assessment on the argument that the rates for occupancy of the Cottage House were such as to guarantee a profit to the hospital. The Managers sued the City and the case was appealed to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. The Court ruled in favor of the hospital. Morton and Woodbury, writing in 1894, trumpeted the decision: | ||

| + | |||

| + | <blockquote>''"The Supreme Court very clearly stated the facts that all the income of the Pennsylvania Hospital is expended in charitable work, and it cannot be regarded as a money-making institution, for any excess over maintenance which is paid by rich patients is used to support others who are destitute of means to make any pecuniary acknowledgment.''"</blockquote> | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 1890, the entrance to the 'Department for Women' was moved from 44th Street and Haverford Avenue to the junction of Powelton Avenue, 44th Street and Market Street. A new gate and security building were constructed at the new entrance. The change was deemed necessary to "render the Hospital more accessible to lines of travel and centres of population." Market Street, rather than Haverford Avenue, had become the principal thoroughfare of West Philadelphia by the late 19th century. Finally, in 1891, "the Managers made a concession of a strip of land extending from Market Street to Haverford Avenue, 80 feet wide, selling it to the City of Philadelphia, on condition that a sewer should be constructed without cost to the hospital, along the course of the former Mill Creek, to connect at both points with sewers already prepared. This construction divides the 113 acres of the Hospital property into two nearly equal parts of upwards of fifty acres each." With this gift to the City of Philadelphia, the Managers allowed 46th Street to become the first thoroughfare to cut through the land of the 'Department for the Insane.' By the 1890 the immediacy of the urban area surrounding the hospital had become a major factor in its daily operations, something was was unforeseen when the first brick was laid fifty years earlier. | ||

==== Medical Staff Directory: 1840-1922 ==== | ==== Medical Staff Directory: 1840-1922 ==== | ||

| Line 117: | Line 135: | ||

The original organization of [[Alienist]] physicians within Pennsylvania Hospital was severely limited. Dr. Kirkbride had laid the foundation of this level of medical hierarchy, which would be maintained to some degree until 1915. This hierarchy places the superintendent as charge and master of all medico-psychiatric issues taking place within the hospital, and an assistant physician to aid to either the male or female departments. Since this was a considerable prestigious post for many psychiatrists it became a starting point for many early careers within the field. However, shifting conceptions of psychiatric care changed in the early 20th century, largely due to legislation lobbied for by Pennsylvania's Committee on Lunacy. Additionally, the 'Food and Drug Act' of 1914 drastically altered the landscape of psychotropics within American Psychiatry. As a result, the Board of Managers of Pennsylvania Hospital, under the guidance of Dr. [[Owen Copp]], reorganized the structure of inpatient treatment and effectively tripled the number of physicians employed to treat the insane. Attending Physicians were also allotted significantly smaller caseloads of patients, from rough 250 per doctor in 1880, to 62 in 1915. This measure also stood in stark contrast to the public mental health facilities of the period, which were notorious for being chronically understaffed. | The original organization of [[Alienist]] physicians within Pennsylvania Hospital was severely limited. Dr. Kirkbride had laid the foundation of this level of medical hierarchy, which would be maintained to some degree until 1915. This hierarchy places the superintendent as charge and master of all medico-psychiatric issues taking place within the hospital, and an assistant physician to aid to either the male or female departments. Since this was a considerable prestigious post for many psychiatrists it became a starting point for many early careers within the field. However, shifting conceptions of psychiatric care changed in the early 20th century, largely due to legislation lobbied for by Pennsylvania's Committee on Lunacy. Additionally, the 'Food and Drug Act' of 1914 drastically altered the landscape of psychotropics within American Psychiatry. As a result, the Board of Managers of Pennsylvania Hospital, under the guidance of Dr. [[Owen Copp]], reorganized the structure of inpatient treatment and effectively tripled the number of physicians employed to treat the insane. Attending Physicians were also allotted significantly smaller caseloads of patients, from rough 250 per doctor in 1880, to 62 in 1915. This measure also stood in stark contrast to the public mental health facilities of the period, which were notorious for being chronically understaffed. | ||

| − | *1) '''[[Thomas Story Kirkbride]]''' - Hospital Superintendent, 1840-1883; President of the [[American Psychiatric Association]] 1862-1870. He remained at the hospital for the duration of his | + | *1) '''[[Thomas Story Kirkbride]]''' - Hospital Superintendent, 1840-1883; President of the [[American Psychiatric Association]] 1862-1870. He originally had intention of being a surgeon, but remained at the hospital for the duration of his career, dying in the superintendent's house in 1883. |

*2) '''[[Edward Hartshorne]]''' - Assistant Physician, 1841-1894. His remained with Pennsylvania Hospital for the duration of his career. His son, Edward V. Hartshorne, would become Treasurer of the Department of Nervous and Mental Diseases after the death of his father. They maintained the same office at 409 Chestnut Street, near [[Pennsylvania Hospital]]'s original campus. | *2) '''[[Edward Hartshorne]]''' - Assistant Physician, 1841-1894. His remained with Pennsylvania Hospital for the duration of his career. His son, Edward V. Hartshorne, would become Treasurer of the Department of Nervous and Mental Diseases after the death of his father. They maintained the same office at 409 Chestnut Street, near [[Pennsylvania Hospital]]'s original campus. | ||

*3) '''Francis Smith''' - Assistant Physician, 1841 | *3) '''Francis Smith''' - Assistant Physician, 1841 | ||

| Line 154: | Line 172: | ||

*36) '''Charles H. Sprague''' - Assistant Physician, 1914 | *36) '''Charles H. Sprague''' - Assistant Physician, 1914 | ||

*37) '''[[Samuel T. Orton]]''' - Clinical Director and Pathologist, 1915-1919; left to become Director of the [[Iowa State Psychopathic Hospital]]. | *37) '''[[Samuel T. Orton]]''' - Clinical Director and Pathologist, 1915-1919; left to become Director of the [[Iowa State Psychopathic Hospital]]. | ||

| − | *38) '''Daniel H. Fuller''' - Assistant Physician, Department for Men, 1915-?; Medical Director for the Department for Males; later sat on the Pennsylvania Committee of Lunacy. Superintendent of [[Adams-Nervine Asylum]]. | + | *38) '''Daniel H. Fuller''' - Assistant Physician, Department for Men, 1915-?; Medical Director for the Department for Males 1922(?); later sat on the Pennsylvania Committee of Lunacy. Superintendent of [[Adams-Nervine Asylum]]. |

| − | *39) '''Horace J. Williams''' - Assistant Physician, Department for Men, 1915-?; later employed by Germantown Hospital | + | *39) '''Horace J. Williams''' - Assistant Physician, Department for Men, 1915-?; later employed as an attending psychiatrist by Germantown Hospital in Philadelphia |

*40) '''George T. Faris''' - Assistant Physician, Department for Men, 1915-1919; ran a private practice in Glenside, PA until his death in 1966. | *40) '''George T. Faris''' - Assistant Physician, Department for Men, 1915-1919; ran a private practice in Glenside, PA until his death in 1966. | ||

*41) '''[[Earl Bond]]''' - Assistant Physician, Department for Women, 1915-?; Medical Director for the Department for Women ?-1922; Psychiatrist-in-Chief, 1922-1935; President of the [[American Psychiatric Association]] 1930-1931 | *41) '''[[Earl Bond]]''' - Assistant Physician, Department for Women, 1915-?; Medical Director for the Department for Women ?-1922; Psychiatrist-in-Chief, 1922-1935; President of the [[American Psychiatric Association]] 1930-1931 | ||

| − | *42) '''Alice H. Cook''' - Assistant Physician, Department for Women, 1915-?, left the field entirely in 1919 to specialize in "diseases of the throat" | + | *42) '''Alice H. Cook''' - Assistant Physician, Department for Women, 1915-?, left the field entirely in 1919 to specialize in "diseases of the throat". |

*43) '''Uriah F. McCurdy''' - Assistant Physician, Department for Women, 1915-? | *43) '''Uriah F. McCurdy''' - Assistant Physician, Department for Women, 1915-? | ||

*44) '''[[Edward Strecker]]''' - Assistant Physician, Department for Women, 1915-1959, Chief Medical Officer 1920-1928; President of the [[American Psychiatric Association]] 1943-1944. | *44) '''[[Edward Strecker]]''' - Assistant Physician, Department for Women, 1915-1959, Chief Medical Officer 1920-1928; President of the [[American Psychiatric Association]] 1943-1944. | ||

| − | *45) '''Annie E. Taft''' - Assistant Physician, Department for Women, 1918-1920 | + | *45) '''Annie E. Taft''' - Assistant Physician, Department for Women, 1918-1920; left to become Custodian of the Neuro-pathological Collection, Harvard Medical School; Special Investigator, Massachusetts Commission on Mental Diseases. |

| − | *45) '''Harry S. | + | *45) '''Harry S. Newcomer''' - Scientific Director of Laboratories, 1922? |

| − | *46) '''Elmer V. Eyman''' - Assistant Physician, Department for Men, | + | *46) '''Elmer V. Eyman''' - Assistant Physician, Department for Men 1921-1935; Chief of Services, 1935-1955; Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Pennsylvania; died in 1955 in Philadelphia. |

*47) '''James M. Robbins''' - Assistant Physician, Department for Men, | *47) '''James M. Robbins''' - Assistant Physician, Department for Men, | ||

| − | *48) '''Norman M. MacNeill''' - Assistant Physician, Department for Women, | + | *48) '''Norman M. MacNeill''' - Assistant Physician, Department for Women, later Professor of Clinical Psychiatry at Jefferson University Medical Center. |

| − | *49) '''Clara L. McCord''' - Assistant Physician, Department for Women, 1920-?; previously of [[Norristown State Hospital]] 1919-1920 | + | *49) '''Clara L. McCord''' - Assistant Physician, Department for Women, 1920-?; previously of [[Norristown State Hospital]] 1919-1920, where she completed her residency. |

| − | *50) '''Baldwin L. Keyes''' - Assistant Physician, Department for Women, | + | *50) '''Baldwin L. Keyes''' - Assistant Physician, Department for Women, (probably only a resident physician) 1922-1923; went on to become President of the Philadelphia Psychiatric Society; he died in 1994, at the age of 100. |

=== Innovation and Expansion: 1912 to 1958 === | === Innovation and Expansion: 1912 to 1958 === | ||

| − | With the dawn of the 20th Century, a particular fascination with professional laboratory science was ushered in. It was posited that by more closely examining the brain and its inner workings, physicians could be able to determine the mysteries of | + | In 1911, the Managers of the [[Pennsylvania Hospital]] appointed [[Owen Copp]] (1858-1933) Physician-in-Chief and Superintendent of the 'Hospital for the Insane'. Dr. Copp was a native of New England, who graduated from Dartmouth College in 1881, and from Harvard Medical School in 1884. One year later, he became a physician in the [[Tauton State Hospital]] for the Insane, in Massachusetts. In 1895 he was named the first Superintendent of the [[Massachusetts Hospital for Epileptics]] at Monson, and in 1899 he was named Executive Secretary of the Massachusetts Board of Insanity (known today as the Massachusetts Department of Mental Health). In this last position, his achievements in improving the care of the institutionalized insane in Massachusetts brought him national attention. Pennsylvania Hospital's appointment was one of his many rewards for a long service record in psychiatry. Shortly after this appointment, he was named the [[American Psychiatric Association]] in 1921. |

| + | |||

| + | Dr. Copp’s administration proved trans-formative for the Hospital for the Insane. He began, as he had done in Massachusetts, by advocating higher standards in the care of the Department’s patients, in contrast to public facilities. Simultaneously, he began to reduce the duration of patient treatment and the number of in-patients present, deciding in many cases that the patient could do better in the familiar surroundings of family and community. This new philosophy was expressed in where the terms "[[Insanity]]" was stricken from all clinical proceedings at the hospital. Shortly thereafter, the term was deemed archaic and pejorative, and quickly fell out of clinical use by the end of the decade. | ||

| + | |||

| + | With the dawn of the 20th Century, a particular fascination with professional laboratory science was ushered in. It was posited that by more closely examining the brain and its inner workings, physicians could be able to determine the mysteries of behavioral disturbance and their alleged correlation with physio-chemical inbalances. Neurologists and Micro-biologists concluded that insanity was a 'disease' of the nervous system, and it should be treated directed as such. Researchers collected brain specimens of deceased insane patients to search for clues about the nature of such pathologies. These early neuro-psychiatrists were no longer convinced that 'humane treatment' alone was sufficient to bring about psychiatric recovery for most of the clinical population. They looked for more allegedly scientific methods in conducting their various therapies. Reflecting this changing view, the hospital's name was changed in January of 1918 from 'the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane' to the "Department for Mental and Nervous Diseases at Pennsylvania Hospital". This name remained with the hospital for the next four decades. It was also during this period that professional nurses and personnel trained in psychiatry replaced the former attendants. | ||

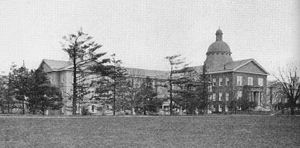

[[File:North.jpeg|280px|thumb|right|The Female Department of the Institute of the Pennsylvania Hospital]] | [[File:North.jpeg|280px|thumb|right|The Female Department of the Institute of the Pennsylvania Hospital]] | ||

| Line 221: | Line 243: | ||

*'''Female Department'''- (1840) the original structure of the department of the insane, constructed 1838-1841. The [[American Psychiatric Association]] would first meet in this building, and it would remain as the primary administrative building for the Institute for the length of its existence. Additionally, it remained in active clinical use until it was sold by the hospital to the City of Philadelphia in 1954, and subsequently demolished. | *'''Female Department'''- (1840) the original structure of the department of the insane, constructed 1838-1841. The [[American Psychiatric Association]] would first meet in this building, and it would remain as the primary administrative building for the Institute for the length of its existence. Additionally, it remained in active clinical use until it was sold by the hospital to the City of Philadelphia in 1954, and subsequently demolished. | ||

| − | *'''North Flats Building'''- (1841) the first expansion to hospital property, as petitioned by Dr. Kirkbride shortly after the completion of the main hospital building. These units were intended for the more acute cases that could not be treated on an ordinary medical unit. They appear to have been reserved for this purpose until the close of the female department a century later. | + | *'''North Flats Building'''- (1841) the first expansion to hospital property, as petitioned by Dr. Kirkbride shortly after the completion of the main hospital building. These units were intended for the more acute cases that could not be treated on an ordinary medical unit. They appear to have been reserved for this purpose until the close of the female department a century later. Demolished in 1954. |

| − | *'''South Flats Building'''- (1841) this building was intended to match the North flats, and was constructed for the same reason, serving the same function throughout its history. | + | *'''South Flats Building'''- (1841) this building was intended to match the North flats, and was constructed for the same reason, serving the same function throughout its history. Demolished in 1954. |

*'''South Fisher Ward'''- (1868) | *'''South Fisher Ward'''- (1868) | ||

| Line 243: | Line 265: | ||

*'''Hospital Auditorium'''- | *'''Hospital Auditorium'''- | ||

| − | *'''Lapsley Pavilion'''- (1922) | + | *'''Lapsley Pavilion'''- (1922) named for Joseph Lapsley Wilson (?) |

=== Campus for the Department of Males === | === Campus for the Department of Males === | ||

| Line 365: | Line 387: | ||

*[http://kirkbridecenter.com/Kirkbride%20Center.pdf Document advertizing the sale of the property] | *[http://kirkbridecenter.com/Kirkbride%20Center.pdf Document advertizing the sale of the property] | ||

*[http://web.mit.edu/wplp/course/f96stud/place/stories/lee.htm Lee Cultural Center- former site of the superintendent's home] | *[http://web.mit.edu/wplp/course/f96stud/place/stories/lee.htm Lee Cultural Center- former site of the superintendent's home] | ||

| + | |||

| + | The Architecture of Madness-Insane Asylums in the United States, Yanni, Carla, University of Minnesota Press (2007) | ||

[[Category:Pennsylvania]] | [[Category:Pennsylvania]] | ||

Latest revision as of 15:56, 26 March 2015

| Institute of the Pennsylvania Hospital | |

|---|---|

Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, as it would have appeared in the spring of 1860 | |

| Established | 1835 |

| Construction Began | Female Dept: 1836 / Male Dept: 1856 |

| Opened | January 1, 1841 |

| Closed | February 1997 |

| Current Status | Active and Preserved |

| Building Style | Pre-1854 Plans (Female bldg), Kirkbride Plan (Male Bldg) |

| Architect(s) | Isaac Holden (female bldg) and Samuel Sloan (male bldg) |

| Location | 111 North 49th St, Philadelphia, PA 19139 |

| Architecture Style | Late Georgian |

| Peak Patient Population | about 500 |

| Alternate Names | *Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane

|

The Institute of the Pennsylvania Hospital, formally Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane, was a private psychiatric hospital operating in West Philadelphia from 1841 until its final closure in the fall of 1997. The building and part of the former campus is currently being leased to Blackwell Human Services and the Kirkbride Center, and remains functional within the human services field; however, it is still owned by the University of Pennsylvania Health System. It was expanded in 1959 to accommodate a changing inpatient population, at which time half the original campus was lost, and the more modern "North Building" was constructed. However, because of changing perception of the practice of psychiatry, and insurance protocol, the facility was forced to close its doors permanently. In 2004, the NHPRC was issued a grant to organize, preserve and make publicly accessible the Institute of the Pennsylvania Hospital's archival collection.

There is a tremendous amount of confusion about the Pennsylvania Hospital in Philadelphia, PA. This is because there were in fact two separate facilities bearing the name. The first, founded in 1751 by Dr. Thomas Bond and Benjamin Franklin was located on Eighth and Pine Streets, and was completed in 1755. This facility is still operational, albeit not for its original purpose. The original structure of Pennsylvnia Hospital is now largely is maintained because of its historic value to the city and state (the modern Pennsylvania Hospital sits behind this building). This original facility found itself overwhelmed by the number of 'lunatic' patients, and regularly had their insane wards overcapacity. The Board of Managers voted to build a second hospital, in what was then rural West Philadelphia, as was the style of such institutions at the time. This second hospital was known as the Institute of the Pennsylvania Hospital, as to draw distinction from their primary facility. This was also the hospital that Dr. Thomas Story Kirkbride was Superintendent, who is regarded as one of the fathers of American Psychiatry. Both facilities were run under the same Board of Mangers during their tenure, but only one had a specific specialization in behavioral healthcare.

Contents

Campus History

Overcrowding at Pennsylvania Hospital: 1817-1834

From its inception, Pennsylvania Hospital admitted both the physically ill and the mentally ill to their historic South Philadelphia campus. Eighteenth and early nineteenth century medical practice was crude, and frequently counter-productive by modern day standards, but the treatment of the mentally ill was particularly harsh. Solitary confinement, bloodletting and involuntary restraints were the order of the day by most physicians. Over time, the proportion of the hospital’s patients who were severely mentally ill increased in size, until it began to become overcrowded, leaving little room for the physically ill. In response, the Board of Managers believed itself obligated to limit the admission of the mentally ill. The west wing of the hospital had been designed and set aside for the mentally ill, but by 1817 it was filled near to capacity and additional space had been set aside for mentally ill patients elsewhere in the facility.

In a published report by the Board of Manager in 1817, the number are brought into focus. Two-thirds of the Hospital’s patients were the mentally ill and the Board of Managers had previously set aside two-thirds of the Hospital’s rooms for their care. The west wing was entirely committed to the care of the mentally ill, and sixteen of the thirty-nine rooms available in the east wing were also devoted to the mentally ill. Though the completed Hospital building was just twelve years old, the Board of Managers had already adopted a policy which limited the number of mentally ill patients for this very reason. There may have been calls for the expansion of the physical site from other administrators, but the Board was unwilling to consider the Hospital’s vacant land for the construction of yet another new buildings. The U.S. census returns for the first decades of the 19th century show increasing pressure: the number of resident staff and patients at the Hospital increased significantly in each decade. The 1820's, in particular, experienced an increase in the average number of resident patients, from less than 150 to more than 200 present at any one time. By 1830 the average daily number of mentally ill patients was somewhere around 115. The demand for the services of the Pennsylvania Hospital must have been near, if not beyond the Hospital’s ability to provide them.

In 1829, Philadelphia Almshouse announced that intended to shut down their center city facility by the fall of 1834, with the intention of transferring all of their services to a new site in the West Philadelphia neighborhood of Blockley. Pennsylvania Hospital’s initial response to the move of the Philadelphia Almshouse was to attempt to purchase its center city land holdings. The "Western Lot" of the Pennsylvania Hospital was open land on the west side of Ninth Street. The Hospital owned the land from Spruce Street on the north all the way south to Pine Street, but only half the distance to Tenth Street. The other half of the block was also open and it was owned by the Almshouse. On the other side of Tenth Street was the city square on which the Almshouse buildings stood. If the western half of the Ninth Street block could be purchased, the way would be clear to expand westward yet another city square.

On May 3, 1830, the Contributors to the Pennsylvania Hospital met and adopted a resolution directing the Board of Managers of the Hospital to purchase the western half of the Ninth Street block from the Almshouse, but not to offer more than $50,000 for the land available. The Board quickly made an offer of the full $50,000, but the Guardians of the Poor refused to sell. Instead, later that same year, they decided to put the land up for sale at public auction. The Board of Managers, meeting on December 27, pf the same year, authorized a bid of $50,000 at the auction, but the minutes of the Board for January 12, 1831 note that the Board’s representatives attended the auction and bid $50,100, but that another bidder had offered more and had purchased the property outright. The winning bid was just $400 more than the hospital had offered: $50,400.75. The new owner planned to develop the site promptly. The Hospital’s Board of Managers, frustrated in their efforts to expand westward, were now forced to consider other options. The Managers began by articulating the Hospital’s need. The minutes of the Board for January 31, 1831 included the following statement:

"The great increase of the number of insane patients which claim the care of this Institution and for whose suitable accommodation and means of relief and restoration the Managers feel deeply concerned has been a subject of frequent consultation. The Board believes it to be a duty to record its sense on this interesting concern and to express its opinion that when sufficient funds can be procured by the contributions of the benevolent, it will be proper to afford adequate space for that description of patients, the present building having become crowded."

The Managers reflected on these minute and then, in April, decided to bring it before the next meeting of the Contributors, which was held on May 2, 1831. The Contributors responded by adopting the following resolutions:

"Whereas, from the great increase of Insane patients under the care of this Institution, that portion of the Hospital appropriated to the reception of such cases is no longer adequate to their proper accommodation. And Whereas it is evident that an Assemblage of Lunatics and Sick patients under the Same Roof is inconvenient and unfavorable to the seclusion and mental discipline essential in cases of Insanity; therefore. Resolved, That we consider it necessary to the interests of this institution and the furtherance of its humane design that a separate Asylum be provided for our Insane patients with ample space for their proper seclusion, classification & employment. Resolved, That the Board of Managers be and they are hereby directed to propose at a future meeting of the Contributors to be called by the Managers when prepared, a suitable site for such an Asylum and the ways and means for carrying into effect the foregoing Resolutions."

These resolutions confronted the Managers with two major challenges for the future of the hospital: where to locate a new hospital building dedicated to the care of the insane, and how to fund its design, construction, furnishings, and subsequent operations. The Board of Managers would struggle with these two questions on and off for the next four years. Their first choice was to build on the city square on the south side of Pine Street, bounded by Pine, Eighth, Lombard, and Ninth streets. In November of 1831, the Managers paid $10,000 for a property on the west side of Eighth Street, between Pine and Lombard. With this purchase they consolidated the Hospital’s ownership of the entire city block. In March 1832, the Managers voted to recommend to the Board of Contributors that the Hospital sell the "Eastern Lot," that is, the city block bounded by Spruce, Seventh, Pine, and Eighth streets. The Board of Managers’ recommendation, though regretted, was agreed upon as the best option available to the Hospital at the time. At their regular annual meeting, held on May 7, 1832, the Board of Contributors adopted the following resolution

"Resolved, that the Managers be authorized to make sale of the Eastern Lot for the purpose of raising funds to erect buildings for the additional accommodation of the Hospital."

Selection of a new site: 1834-1840

The disposition of the Eastern Lot, however, proved to be a very slow process. More than a year passed before the Board of Managers authorized the first sales of land, and several years passed before the last of the building lots were sold to private interests. In the interim a division took place among hospital administrators about how to proceed with expansion, and how to properly address the rising census of insane patients. Economics necessity had them bound to inpatient psychiatric care for the time being. This had been a mounting problem for several decades prior because of the reversal of hospital policy under Dr. Benjamin Rush, stating that lunatic should be treated on the regular medical unit of the hospital.

At a meeting of the Board held on January 27, 1834, progress was reported for possible construction on the south lot of the property; but just a month later, on February 24th, the committee overseeing this capital improvement was dissolved. The minutes of the Board of Managers contain no further reference to plans for a new building on the South Lot of the hospital. It is likely that the proposal must have met too much resistance from administration. Another year passed without any change to the status development of this project. The Sale of building lots, carved out of the former Eastern Lot progressed, but only very slowly. Finally, on May 8, 1835, the Board of Managers decided to call a meeting of the Contributors. The Contributors concluded by adopting the following resolution:

Resolved, that in the opinion of this meeting it is expedient that the Lunatic department of the Pennsylvania Hospital should be removed from the City of Philadelphia to the country in its vicinity, provided that the removal can be effected upon such a plan as will promote the comfort and improve the health of the patients and admit of the superintendence and control essential to a good administration of the institution. Resolved, That the Managers of the Hospital be, and they are hereby requested to prepare and report to the Contributors at their next meeting a plan of removal agreeably to the preceding resolution; embracing in their report the location in point of distance from the City, the general structure of the buildings to be erected, the details of the organization for superintendence and control, the funds and resources of the Corporation available for this object, and the probable cost; with such facts and remarks as they may think it expedient to communicate for the information of the Contributors.

The Managers appointed an 'ad hoc' committee to respond to these resolutions and to report to the Board. On August 4, 1835 the committee reported back to the Board. The members of the committee reported their preference for a new hospital for the insane inside the city limits, but because popular sway among the members of the board lead to adopting a resolution to locate the new hospital in a more rural atmosphere. The long debate over the location of a new hospital seemed finally concluded, but the issue of funding was still outstanding. The committee estimated that the cost of land, design, construction, and furnishings for a new hospital for the insane would be $203,000; that the annual operating expenses of the hospital would be around $25,000 per anum; and that the annual revenues from paying patients would be about $12,500. The interest on $200,000 in capital funds would be required to pay the remaining annual cost of $12,500. The total estimated for construction would be $403,000, a sum the committee termed "immense." (roughly equivalent to 40 million USD in 2013).

The hospital moved to purchase a 101-acre farm in West Philadelphia in 1835 from Matthew Arrison, a local merchant. In March of 1836 the Board of Managers selected an English architect, Isaac Holden, to design the new buildings. The cornerstone for this new facility was laid on July 26, 1836 on the corner of 44th and Market Streets, which would later become the Female Department of the hospital. The design of the new Hospital for the Insane followed certain fundamental decisions. First, the Board and its architect maintained the Haverford Avenue orientation of the country estate. The entrance to the new hospital buildings remained on Haverford Avenue and the brick mansion at the top of the hill was not disturbed, as it would soon become the house of the hospital superintendent. The new structures were sited behind the big house and towards the southeast end of the 101 acres. Second, in order "to have control of all the springs in the neighborhood of the pump-house," the Board made two purchases of land, which together added approximately ten acres to the east end of the grounds. Third, they enclosed forty-one acres of the land, including the two new purchases, by building a large stone wall, 5,483 feet in length and 10½ feet high around the hospital's primary enclosure. In 1839, when the construction was only about half finished, Holden took ill and returned to England. Construction was completed from his original designs.

The question of selecting an appropriate superintendent was complicated because of the absence of other large psychiatric facilities in the America at the time. Locally, only Friends Hospital, then known at the Frankford Asylum, was operational in treating psychiatric disorders, and was only financially viable because of large donations offered from the Society of Friends. The Board of Manager voted on October 12, 1840 and elected to hire the thirty-one year old Alienist physician, Dr. Thomas Story Kirkbride, as the head of the new hospital, which would open the following January. Dr. Kirkbride was Pennsylvania native, born in Morrisville, where his family resided, and graduated from the University of Pennsylvania Medical School only a few years prior in 1832. Kirkbride had served three years as a resident physician at Friends Hospital for the Insane in Frankford township, a rural setting about five miles northeast of the City of Philadelphia. In 1835 he returned to Philadelphia and opened a general practice. Just before his appointment in 1839, he married the daughter of one of the former Managers of the Pennsylvania Hospital. He accepted the Board’s appointment and immediately took control of the new department.

Under Dr. Kirkbride: 1840-1883

In January 1841, the Board of Managers opened the new hospital buildings and gradually, over the next few months, transferred ninety-three insane patients to the West Philadelphia campus. A Philadelphia newspaper, the North American, reported on the progress of the move in its issue of March 1, 1841:

"Removal of the Insane- During the past week, about sixty of the insane patients were removed from the Pennsylvania Hospital to the new building belonging to the institution, erected over the Schuylkill for patients of this description. The removal of the remainder, some forty or fifty in number, will shortly be effected."

Another Philadelphia newspaper, the Public Ledger, on 29 May, also reported on the new hospital:108

"Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane- The contributors to the Pennsylvania Hospital lately finished the main buildings of their new Hospital for the insane. This is situated about two miles west of the Permanent Bridge, between the Haverford and West Chester roads. The number of patients which can be accommodated there is stated to be 200. Poor patients are supported by the Hospital, other pay according to their ability. The lowest rate of board for a Pennsylvanian being three dollars fifty cents per week, or $182 per annum – for an inhabitant of any other State, $5 per week, or $250 per annum. The whole receipts go to the support of the Institution. The arrangements are on a fine scale, board cheap, situation healthy, and treatment judicious."

At the regular, annual meeting of the Contributors to Pennsylvania Hospital, held on May 3, 1841, the Board of Managers reported that the main new building of the 'Hospital for the Insane' was officially completed and occupied. They also provided the Contributors with a final accounting of the project’s ongoing venues and expenditures. The purchase of the 101-acre Arrison farm estate, as well as two subsequent purchases of adjoining land, totaling ten acres had together cost $33,058.81. Design and construction had cost $265,000. Total expenditures to date were therefore $298,058.81, significantly under the previous expectations. This sum was more than balanced by the proceeds from the sale of the city square to the east of the Eighth Street, $154,226.24; by the proceeds from the sale of the partial squares to the west of Ninth Street, $120,000.00; and by the accumulated interest on the sale of these lands, $48,883.08. Total revenues to date were therefore $323,109.32, leaving $25,050.51 in the hospital building fund.

The new superintendent, Thomas Story Kirkbride, gained national renown because of his particular clinical methods. He developed a more humane way of treatment for the mentally ill that became widely influential within American Psychiatry. Today, the former Institute campus exists as a multi-purpose social-service facility. The new hospital, located on a 101-acre (0.41 km²) tract of the as yet unincorporated district of West Philadelphia, offered comforts and a “humane treatment” philosophy that set a standard for its day. Unlike other asylums where patients were often kept chained in crowded, unsanitary wards with little if any treatment, patients at Pennsylvania Hospital resided in private rooms, received medical treatment, worked outdoors and enjoyed recreational activities including lectures and a use of the hospital library. The campus originally featured one, but later, two hospital buildings, which were separated by a creek and pleasure grounds.

The first building was a long thin building located west of the Schuylkill River. This building would eventually become the female department. Though the building does reflect the Kirkbride Plan it was actually constructed before Dr. Kirkbride was given full supervisory duties. Construction began under the control of architect Isaac Holden, but later illness forced Issac to return to his home country of England. The building was then finished by a young Samuel Sloan, who had previously worked as a carpenter on Eastern State Penitentiary. Sloan finished the building in 1841 using Holden's plans. The building was a rather simple design compared to later Kirkbride Plan buildings. Constructed of cut limestone, it was three stories tall with a central administration section flanked on either side by a set of wings. The top of the administration section was crowned with a large dome. On both the front and back of the administration section were stone porticoes. The interior of the building was well furnished, the lavishly carpeted corridors were twelve feet wide. The building features iron stairs, well lighted wards, and iron water tanks in the dome over the administration section, which provided fresh water to all of the building.

While the main building of the new Hospital was completed, Superintendent Kirkbride petitioned the Managers that it was not adequate for "the noisy, violent and habitually filthy patients." He requested the Managers and Contributors to approve the construction of two detached buildings for this particular class of patients. The Contributors, at their May 1841 meeting, did approve the construction of these additional structures. These ward building were much smaller, one story, "W" shaped buildings. They were frequently used to house the noisy, disruptive and violent patients, so that they wouldn't disturb the calmer, more manageable patients in the main hospital building.

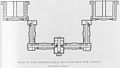

Superintendent Kirkbride developed his treatment philosophy based on research he conducted at other progressive asylums of the day including the asylum at Worcester, Massachusetts. Out of his philosophy emerged what would become known as the Kirkbride Plan, which created a model design for psychiatric hospital that was employed across the United States throughout the 19th century. This plan would be used for the hospital’s second building. On July 7, 1856, the cornerstone for a new building, built with the money from individual contributions, was laid at 49th and Market Streets, five blocks west of the original building. The new structure, which was to house only male patients, was dubbed the Department for Males, while the original building officially became known as the Department for Females. Dr Kirkbride commissioned Architect Samuel Sloan to design the new building. Built of stone and brick, the new building was laid out, as Kirkbride expressed, "in echelons." A large rectangular building, 3 1/2 stories tall, with gable roof and central dome, and a 2 story pedimented portico on its western facade, provided the central focus of the hospital and also housed its administrative offices. Extending from the center of this building to the north and south are two symmetrical wings about 250 feet long, 3 stories tall with gable roofs and ventilation cupolas at their furthermost termini. These wings were in turn connected to another pair, which extended to the east approximately 230 feet, paralleling each other, and of the same general appearance. At each terminus of the these rear wings was a final E-shaped wing which extended out approximately 250 feet. The north E wing housed troublesome patients, and the south E wing has since been removed. No wings are exactly in line, thus allowing fresh air to reach each wing on all four sides. Each of the patients' rooms in the wings had its own fresh air duct, the air being driven in from the towers at the terminus of each wing. There were 16 wards in the hospital, one for each of 16 distinct classes of patients, and each ward had its own parlor, dining room, and bathroom. Outside, there were gardens, shops, and walks for the patients.

For the first seventy years of its existence Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane steadily increased in its size and clinical complexity. As early as February 1844 the trend for expansion had been firmly established. The Public Ledger took note of the statistics in Kirkbride’s annual report and published the following brief article: We have received a copy of the Report of the Managers of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane for 1843. There were 140 patients admitted during the year, 126 have been discharged or died, and there remain 132 under care. There were cured 68, much improved 7, improved 14, stationary 20, died 17 – total 126. The Report contains a number of statistical tables, showing the number and sex of the persons admitted since the opening: their ages, occupations, condition, nativity, country, and the causes which produced insanity in them, with the duration and number of the attacks. Since the opening of this Hospital, three years since, there has been a steady increase in the number of patients admitted, and the number under care at one time has constantly been augmenting. The total number under care in 1841, was 176; in 1842, 238; in 1843, 258.

Expansion of the site continued, and by 1851, just ten years after its opening, the Hospital was "inconveniently crowded", though the [Annual] hospital report stated that "the general good health which then prevailed, enabled us to receive all the cases that were brought to the Hospital, although much difficulty was often experienced in accommodating them." Two years later, the annual report for 1853 became more grim, and stated:

"during the entire year, the institution has been rather more than comfortably filled, the average number for the whole period, as shown above, being 229, while 220 is regarded as the capacity of the building. Anxious to receive all who desired admission, we have at no previous time refused any suitable applicant; but during a part of the year just closed, we were for a time compelled, although with great reluctance, to decline receiving patients, except under the most urgent circumstances."

By May 1854, Dr. Kirkbride had convinced the Hospital’s Board of Managers of the need to build a second, larger hospital building on the West Philadelphia grounds, and to separate the patients by sex, which was the custom of the era. The Managers authorized a $250,000 fundraising campaign and published an "Appeal to the Citizens of Pennsylvania for Means to Provide Additional Accommodations for the Insane." By the spring of 1856 the campaign had raised $209,000 in gifts and private pledges. In March of that year, the Managers authorized the design and construction of a separate building to house, the "Department for Males", and it appointed a building committee to oversee the work. The committee selected Samuel Sloan as its primary architect. Sloan took due consideration of Dr. Kirkbride's suggestions, as well as the guidelines of his predecessor in the Department for Females. Construction began in July, and in October the Managers conducted a ceremony in West Philadelphia in which the Mayor of Philadelphia, Richard Vaux, laid the hospital cornerstone. The new building opened three years later, in October 1859, with a separate entrance on 49th Street, midway between Haverford Avenue and the West Chester Road (renamed Market Street). The new building’s total cost was $322,542.86, but additional expenses– a boundary wall, carriage house, carpenter shop, brought the total expenditure to approximately $350,000.17.

The new 'Department for Males' was magnificent, with "a handsome Doric portico of granite in front, and is surmounted by a dome of good proportions. The lantern on the dome is 119 feet from the pavement below, and from it is a beautiful panoramic view of the fertile and highly improved surrounding country, the Delaware and Schuylkill Rivers, and the city of Philadelphia, with its many prominent objects of interest." In 1860, the original building, now the "Department for Females," was extensively renovated, and placed in the same condition as the new building. The capacity of the Department for the Insane was thereby doubled, from 220 patients to 470 total. It was now an extraordinary large institution, one of the first to be designed and organized in accordance with the 1851 guidelines of the American Psychiatric Association (guidelines which had been authored by Kirkbride himself), but it was also was one with critics. Dr. Meigs, in his 1876 history of the Pennsylvania Hospital, acknowledged many of the problems, but defended the hospital, stating:

"Occasionally, an outcry has been raised against what the objectors have been pleased to call ‘palaces for the insane.’ What would these critics have? A building to contain from 200 to 250 patients, with officers, attendants, cooks, bakers; with offices, sitting-rooms, bed-rooms, bath-rooms, water-closets, ironing-rooms, and kitchens; can such a building be other than large and imposing? Is it a palace, simply because it is vast? This element of size cannot be avoided, and the question reduces itself to the simple alternative, shall the so-called palace be imposing by the hugeness of its deformity, or by fitness for its purposes, and by the beauty of its outlines?But such cavils against insane hospitals come only from the thoughtless. I have always felt, and shall always feel, grateful to the Managers of this Hospital, for the fine taste they have shown in the style and architecture of these buildings. Amongst the pious uses of money is the embellishment of cities.

We cannot be too thankful that the buildings for the insane were made handsome, striking, and picturesque. Some one of these cavillers, or any one of us, may yet have to place in an insane asylum some one near and dear to us. Who knows what the morrow shall bring forth? If it were to be so, should we choose a building with the air of a prison, penitentiary, or great uncouth and rambling hotel, or a well-proportioned, attractive, and imposing house for the poor afflicted one to dwell in? No, for one, I rejoice in these handsome and attractive buildings for the insane. I think it must be only a weak, pitiful mind, and a cruel soul, that would refuse to these afflicted ones such sweet pleasures of the senses as we may be able to give them."

Despite the critics, expensive improvements in the physical plant continued for several years. In 1868, 1873, 1880, 1888, and 1893, five new buildings were constructed for women patients and called the South Fisher Ward, the North Fisher Ward, the Mary Shields Wards, the Cottage House or Villa, and the I.V. Williamson Wards, respectively. In 1864 the women’s "Gymnastic Hall" was funded and constructed and in 1890 a gymnasium was also constructed for the men's campus. At the close of the 19th century the facilities of the hospital for the Insane rivaled those of any similar institution in the nation.

Likewise, the staffing of the 'Hospital for the Insane' steadily expanded through the 19th century and well into the early 20th. A broadly useful view of the hospital may be obtained from the decennial U.S. census returns. In 1850, Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane housed 251 resident patients, and 85 resident staff; in 1860, 276 patients, and 119 staff; in 1870, 327 patients, and 167 staff; in 1880, 376 patients and 218 staff; in 1900, 437 patients, and 267 staff; and in 1910, 446 patients and 291 staff. A community that totaled 336 persons in 1850 more than doubled in size to one that totaled 737 in 1910. In addition to its rapid growth, it was noted for being an extremely self-contained community. There were the officers– the superintendent, the stewards, the matrons, the physicians– and those who cared directly for the patients, such as: the attendants (later called nurses); but even as early as 1850 there were also farm laborers, cooks, men to attend to the fireplaces which heated each room, carpenters, coachmen, and gate keepers, all of them resident staff, living on the grounds of the hospital proper. The number of work specializations increased with each decade, until, in 1910, there were also gardeners, waitresses, laundresses, cleaners, seamstresses, even a masseur, a pharmacist, a buyer of clothing, a bookkeeper, a storekeeper, an engineer, and two messengers. The Department was a neighborhood unto itself. It should also be noted that throughout this period, while the patients were almost all native born, the majority of the staff were natives of Ireland. If these arrangements seemed acceptable in the 19th century, they certainly were challenged by the changing ethnic demographics of West Philadelphia in the 20th century.

Turn of the Century: 1883 to 1911

The Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane flourished under Kirkbride until his death on December 16, 1883, though for decades after his death, Philadelphia natives colloquially referred to the hospital as "Kirkbride's." Dr. John Chapin, the former Superintendent of the Willard State Hospital in New York, assumed the role of Superintendent of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane after Kirkbride's demise, following a lengthy election by the Board of Managers. The Board had spent ten months making their selection, which was precarious because of the fame and reputation of Kirkbride. Chapin officially assumed this role on September 1, 1884, and held that office until the resignation from his duties in 1911. He was directly succeeded by Dr. Owen Copp, who initiated a School of Nursing for Men at the Hospital. Dr. Chapin appoints Leroy Craig as the first director of 'the Pennsylvania Hospital School of Nursing for Men'. Craig gains notoriety as the first male superintendent of a male nursing school in the country. Similar schools had previously been established locally at Friends Hospital and Norristown State Hospital. The new school of nursing was devoted to training male nurses in generalized nursing practices, as well as the specialization in the disciplines of psychiatric care.

It is during the second part of the hospital's history that the particulars of its operations change dramatically. Starting in 1876 the number of patients admitted to the inpatient based upon charity began to drop, which was credited to rise of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania's involvement in psychiatry as a matter of the public health. This rise in psychiatric care was found to be startling in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. When Kirkbride opened the new asylum in 1840 there were a total of 275 beds available for those who suffered from mental illnesses. shared by the facility and Friends Hospital. By 1895, 7,000 inpatient beds had been created between various: private and state hospitals, as well as local sanitariums. While this trend would continue well into the 20th century, Pennsylvania Hospital's inpatient population maximum would not change from the five-hundred beds it was allotted following its expansion in 1853. While the Institute would remain an industry leader, it was longer the only psychiatric facility available to the public regionally.

In contrast to many state facilities, the physical site and grounds of the 'Hospital for the Insane' were indeed "of the first class" status, and would remain so in public opinion. So too was the number of staff attending, and the staff’s general care of their patients. AS the 19th century progressed, it became clear that the 'Hospital for the Insane' was increasingly becoming an elite institution. West Philadelphia, however, was growing up all around the Hospital and between 1886 and 1891 the Managers of the Pennsylvania Hospital took four actions which demonstrated the extent of the city’s presence. The first was perhaps the most significant. In May 1886, the Contributors to the Pennsylvania Hospital authorized the Managers "to purchase such area of land, within a reasonable distance from the city, not exceeding 500 acres, in order to prepare a site for such future adjuncts or additions to their Hospital as may hereafter be required or found desirable." In June of that year, the Managers formed a committee which began buying land in Newtown Square, Delaware County. By May 1891, five years later, the purchases totaled "607 acres". The land was designated for the future of the 'Hospital for the Insane', and in 1892 the Managers announced tentative plans for building on the acreage. However, this would never materialize.

Then, in 1888 and 1889, the Board of Managers clashed with the City of Philadelphia over their charity status and the issue of medical exemption from city taxation. In the summer of 1887, the Board of Managers authorized the construction of the "Cottage House" or "Villa" for female patients at the hospital. The new structure opened in June 1888 to mild fan fair. The municipal government made a claim against the hospital for water supply to the new building, justifying its assessment on the argument that the rates for occupancy of the Cottage House were such as to guarantee a profit to the hospital. The Managers sued the City and the case was appealed to the Pennsylvania Supreme Court. The Court ruled in favor of the hospital. Morton and Woodbury, writing in 1894, trumpeted the decision:

"The Supreme Court very clearly stated the facts that all the income of the Pennsylvania Hospital is expended in charitable work, and it cannot be regarded as a money-making institution, for any excess over maintenance which is paid by rich patients is used to support others who are destitute of means to make any pecuniary acknowledgment."

In 1890, the entrance to the 'Department for Women' was moved from 44th Street and Haverford Avenue to the junction of Powelton Avenue, 44th Street and Market Street. A new gate and security building were constructed at the new entrance. The change was deemed necessary to "render the Hospital more accessible to lines of travel and centres of population." Market Street, rather than Haverford Avenue, had become the principal thoroughfare of West Philadelphia by the late 19th century. Finally, in 1891, "the Managers made a concession of a strip of land extending from Market Street to Haverford Avenue, 80 feet wide, selling it to the City of Philadelphia, on condition that a sewer should be constructed without cost to the hospital, along the course of the former Mill Creek, to connect at both points with sewers already prepared. This construction divides the 113 acres of the Hospital property into two nearly equal parts of upwards of fifty acres each." With this gift to the City of Philadelphia, the Managers allowed 46th Street to become the first thoroughfare to cut through the land of the 'Department for the Insane.' By the 1890 the immediacy of the urban area surrounding the hospital had become a major factor in its daily operations, something was was unforeseen when the first brick was laid fifty years earlier.

Medical Staff Directory: 1840-1922