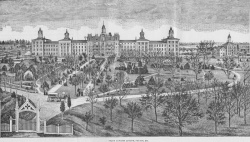

Fulton State Hospital

| Fulton State Hospital | |

|---|---|

| |

| Established | 1847 |

| Opened | 1851 |

| Current Status | Active |

| Building Style | Kirkbride Plan (Demolished) |

| Architect(s) | Solomon Jenkins (Original Building) & Morris Frederick Bell (Later modifications) |

| Alternate Names |

|

History[edit]

In 1847, the Missouri General Assembly enacted legislation to establish an asylum for the insane in the central area of the state. This institution was to provide physical care for societal "lunatics." Several counties were encouraged to bid for this institution. Callaway County was able to produce $11,500 and 500 acres of land, thus winning the bid. Fulton State Hospital, the first public mental institution west of the Mississippi River in 1851, admitted its first 67 patients in December.

The original building was three stories high, excluding the basement and attic. It contained 72 rooms and housed the same number of patients. The center of the building was reserved for a patient dining area, and lodging rooms for officers, attendants, and laborers. All employees of the hospital were required to live on the grounds, and had to obtain special permission from the Superintendent in order to leave. The hospital was almost totally self-sufficient at this time. By maintaining sewing rooms, vegetable and straw houses, raising their own food, pumping water from underground wells and streams, and making their own soap, the hospital was similar to a small city, requiring few resources from outside its grounds.

According to State Biennial Reports, several probable causes of mental illness were determined in the first cases admitted. Among the more unusual causes were indigestion, religious anxiety, disappointed love, intense study, and jealousy. Epilepsy and tuberculosis were the two most common causes. As psychiatry was virtually an unexplored field, primary emphasis was placed on the physical needs of the individuals and maintaining a system of order within the hospital. The majority of individuals at this time were aged 20 to 40, and ranged in occupation from broom makers to lawyers. Early methods of calming these individuals included the use of hydrotherapy (running cool water over individuals' wrists and ankles to reduce metabolic rate), sensory deprivation chairs (chairs with straps and a hood to be lowered over the individual's head, depriving the person of his senses), twirling chairs (devised to spin individuals in rapid circles in order to separate the "humors" of the brain), and needle cabinets (steel boxes in which individuals sat in while high pressure water was pumped directly onto their skin). Strain jackets and shackles were used to restrain individuals. All of these seemingly cruel tactics served the purpose of preventing individuals from causing physical harm to themselves or others during their psychotic episodes.

As technology advanced, these early strategies were abandoned and a more curative approach was adopted. The hospital developed a motto that required its employees to treat patients as friends and brothers as opposed to inferiors. According to Pinel, it was believed that "goodness is the most effective of remedies, and justice the most impressive of authorities." Any employee not abiding by this motto was released from duty.

In 1852, the idea that religious instinct survives the wreck of the intellect initiated the construction of the first chapel for individuals' use. Music played during religious services seemed beneficial to these individuals and served as a rudimentary form of what was later to become music therapy. In 1859, Dorothea Lynde Dix visited the hospital. Through her, the hospital received a large number of amusement items as well as cash donations. Dix was a pioneer in the movement to establish mental health facilities. She thought it unnecessary to keep mentally disturbed persons in jail because of their burden on society. She appealed to lawmakers to establish a facility for these individuals where they could receive proper care. A period of local disorder brought about by the Civil War forced the hospital to close in 1861, and a large number of individuals from the St. Louis area were returned home. The hospital building was used as a barracks to house Federal troops. Due to the sudden influx of these persons back into the St. Louis community, St. Louis County built an asylum in 1948 that became the St. Louis State Hospital. Fulton individuals were transported by steamboat to this new hospital.

The Fulton hospital reopened in 1863 with approximately 125 individuals. Two years later the first black individuals were admitted to the hospital and cared for on a separate "colored" ward. By the early 1870s individuals engaged in work as well as recreational amusements on the hospital grounds. These activities kept patients' minds and bodies active while increasing their self esteem. Eventually, these activities evolved into what is today called recreational and occupational therapy.

By the turn of the century, many changes had taken place within the hospital. In 1910, the patient census had passed the 1,000 mark. Over time, crowding produced expansion of facilities. The original building now included two new large wings on either side. Twenty-nine wards were established and a special unit was built to house the criminally insane. Elevators were installed in various areas to aid disabled patients and alleviate confinement to rooms. Other facilities in operation on hospital grounds included an infirmary, kitchen, bakery, chapel, and museum. Stephens Park provided a place for patient recreation. Technological advancements aided in the maintenance needs of the hospital. Marsh pumps were installed pumping 35,000 gallons of water per day throughout the institution. Dynamos were purchased providing electric lights, a telephone system was setup, and a fire brigade was organized to further ensure patient safety.

Treatment approaches in the mid-1900s advanced to keep up with the rapidly growing hospital. Electrotherapy, insulin and metrozol shock treatment, and prefrontal lobotomies were all performed with the more serious patients. Emphasis in treatment of patients began to shift from merely physical maintenance to encompass mental demands as well. Patients engaged in occupational and recreational therapy, lessening the need for restraining techniques. As the use of restraints declined, an "open door" system was implemented with individual clothes lockers to encourage cleanliness. Holidays and special activities were planned to boost morale. Patient interaction became further possible with the building of a canteen. Finally, patient classifications on wards were designed. Epileptics, dangerous patients, tubercular patients, and prisoners were all separated.

By the early 1930s, physical ailments of patients were treated on hospital grounds. Physicians, dentists, and pathologists were employed in this task. Unfortunately, due to the vast number of patients, the doctor-patient ratio was approximately 1 to 543. In 1934, programs to educate the community about the prevention and treatment of mental diseases evolved. The medical staff aided in the task by speaking on several topics such as "modern treatment and methods of mental diseases" and "value of recreational therapy in mental hospitals." A result of this community education was the development of a volunteer program. The volunteer program provided social interaction for the individuals, as well as a chance for lay people to see and understand firsthand the disease of mental illness. Its overwhelming success is still apparent today, as volunteer interaction remains an important part of an individual's treatment.

The maximum-security Biggs Building was completed in 1940. It housed eight wards, with a kitchen and dining room, hydrotherapy facility, and a hospital ward. Individuals admitted into the Biggs unit were those found not guilty by reason of insanity, criminal sexual psychopaths, those awaiting pre-trial evaluation, and individuals incompetent to stand trial. Today, the Biggs Building has been expanded to include a female forensic unit. Prior to its establishment, women were sent to prison for murder and other serious crimes, or were placed elsewhere in the mental health system.

On March 15, 1956, a disastrous fire destroyed the administration building and the two adjoining wings which housed nearly 250 individuals. Fortunately, no lives were lost; however, many patient and hospital records were destroyed. Students from Westminster College, along with Fulton, Jefferson City, Columbia, and Mexico fire fighters, attempted to salvage whatever possible. The cost for wrecking fire damaged buildings exceeded $1,014,000, and the hospital had to suspend admissions for a few months. Appropriations made afterward allowed for rebuilding as well as the addition of a Geriatrics unit.

In the last half of the 1960s, the Hearnes Unit was built for the purpose of treating children. The main goal of the unit was to simulate normal life and convert maladjusted children into normal citizens. Children were accepted on a limited basis, with the highest census being 170. This facility was the first juvenile treatment center of the Mental Health Division. The 1970s were a time of implementing innovative outpatient treatment programs for problems resulting from specific needs. The average caseload in the early '70s was around 1,199. Outpatient programs provided aid to those afflicted by mental retardation, personality disorders, social maladjustment, and many other neurotic problems. In 1975, approximately 5,300 individuals appeared on the rolls of the hospital. Of these, however, only about 1,180 were physically present. Some 1,000 elderly individuals were placed in nursing homes, where their care and supervision could be attended to. In addition, hospital-based and satellite community clinics served some 2,600 outpatients, and several hundred individuals were on convalescent leave status to determine their readiness to resume community living.

Near the close of the 1970s, Fulton State Hospital applied for Medicaid funding of Geriatric individuals. This was the first time Medicaid funds were used for a psychiatric facility in the Division of Mental Health. Throughout the 1980s, the primary diagnoses of individuals hospitalized at Fulton State Hospital were schizophrenia and manic-depression. A new emphasis was placed on the reintegration of recovering individuals into the social setting. Treatment was expanded to include individual and group therapy, drug therapy, vocational rehabilitation, physical and psychological testing, speech and hearing services, education, and employment-preparedness projects.[1]

Five years after former Gov. Jay Nixon won legislative approval for the $211 million project, the Missouri Department of Mental Health opened the new Nixon Forensic Center in early July 2019. The new building is shaped like a backward “S” with wide hallways, high ceilings and ample use of natural light. The 500,000-square-foot complex features 300 beds separated into 12 living groups of 25 each. Fulton State Hospital consists of treatment units for high and intermediate security patients (Nixon Forensic Center, 300 beds), individuals with developmental disabilities (Hearnes Forensic Center), and the Sexual Offender Rehabilitation and Treatment Services (SORTS) program (Guhleman Forensic Center).

Books[edit]

- Evolution of a Missouri Asylum: Fulton State Hospital, 1851-2006 by Richard L. Lael, Barbara Brazos, and Margot Ford McMillen

Images of Fulton State Hospital[edit]

Main Image Gallery: Fulton State Hospital

References[edit]

- ↑ From the Missouri State Department of Mental Health website