Hudson River State Hospital

| Hudson River State Hospital | |

|---|---|

| |

| Established | 1866 |

| Construction Began | 1868 |

| Construction Ended | 1895 |

| Opened | 1871 |

| Closed | Jan 25, 2012 |

| Current Status | Closed |

| Building Style | Kirkbride Plan |

| Architect(s) | Frederick Clarke Withers (Grounds: Frederick Law Olmstead & Calvert Vaux) |

| Architecture Style | Victorian High Gothic / Victorian Gothic |

| Alternate Names |

|

Contents

[hide]History[edit]

The following is from a 1916 report[edit]

In 1866, eleven years after the strong memorial presented to the Legislature by county superintendents of the poor setting forth the neglected condition of the insane and recommending the establishment of two additional state hospitals for their care and treatment, Governor Fenton appointed five commissioners to secure a suitable site "on or near the Hudson River below the City of Albany, upon which to erect the Hudson River Asylum for the Insane." The offer of a 208-acre farm jointly by the County of Dutchess and the City of Poughkeepsie was accepted and during the following year the Legislature appropriated $100,000 for the construction of one building. Meanwhile there had been appointed a Board of Managers of nine members, who had selected as superintendent Dr. Joseph M. Cleaveland, who had received his training in the parent institution at Utica. With the appropriation above referred to the managers procured an additional 84 acres of land and authorized a New York firm of architects, Messrs. Vaux, Withers & Co., to prepare plans and specifications for a hospital to accommodate 250 patients of each sex. At the same time extensive plans were adopted for the improvement of the grounds. No patients were received until 1871 and only seven patients were accommodated during that year.

In 1872 the total cost of the buildings thus far reached $1,000,000 with current accommodations for only 212 patients. The State Comptroller criticized the managers for spending such an excessive amount of money and having little to show for it. In the managers reply it was pointed out that after the close of the Civil War, and especially by the enactment of the new eight-hour law, the greatly increased cost of both labor and material was responsible for the high costs. They asserted that the plan followed by them of constructing the hospital by day's work rather than by contract was the best to follow; further, that "although the hospital has cost money, it is worth the money" and that the Governor, Comptroller and other state officials had inspected the buildings and had approved the plans and specifications and general scheme of construction. However, appropriations for additional work of any magnitude were deferred until 1875, when the Governor, with legislative sanction, appointed a building superintendent to control the further construction of the hospital buildings. It was also ordered that all building operations be done under contract. Although $1,500,000 were expended in the 18 years intervening between 1868 and 1886, accommodations for only 400 patients had been provided.

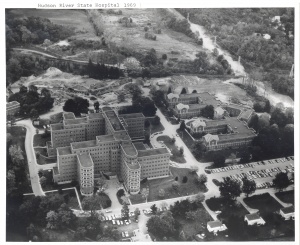

In March, 1893, Dr. Cleaveland resigned and was succeeded by Dr. Charles W. Pilgrim, who had previously served as superintendent of the Willard State Hospital. With appropriations granted in 1891 a group of cottages had been completed on a distant portion of the hospital grounds for the accommodation of 320 of the insane remaining in the poorhouses of the state. Dr. Pilgrim also found it possible by readjustment of sitting rooms and dormitories to provide accommodations in the main institution for 302 additional patients. Thus the capacity of the institution was increased from 800 beds in 1890 to 1400 in 1893. The central group of buildings, nearly a mile from the main establishment, was enlarged and greatly improved. In 1898 the huge north wing was added, thus increasing the capacity further to 1970. The reception building, designed and equipped specially for the care and treatment of new and supposedly curable cases, was occupied in 1908, as was also the building known as Inwood, designed specially for the care of the chronic insane. The capacity was further increased by these buildings to 2708. The land now comprised in the grounds and buildings has reached 1000 acres.

The title of this institution adopted at the time of its organization is the Hudson River State Hospital.

The different groups of buildings permit an excellent classification, the tubercular and epileptic, the most troublesome and dangerous of all, being removed from the general wards. The hospital is thoroughly equipped and has every facility for doing the most advanced psychiatric work. The staff consists of 20 physicians, and there are 608 employees engaged in the work of the hospital. Superintendent Pilgrim served as State Commissioner in Lunacy for one year, 1906, on leave of absence from the hospital.

The main hospital buildings are located on a beautiful slope which extends to the banks of the Hudson River and affords a variety of beautiful vistas.

A trained pathologist, who devotes his entire time to studies of the brain and nervous system, is one of the valuable adjuncts of the hospital. Another feature of merit is a thoroughly organized training school for nurses, which is conducted with enthusiasm and success by the medical staff. A no less important feature is the course of training for beginners, t. e., ward attendants, all of whom are given a course of five lectures, one by the first assistant physician, on the general subject of insanity, the necessity of forbearance, especially on the part of attendants detailed to escort patients to the hospital, and general features of the insanity law; the remaining five on practical ward work, bathing, dining room and kindred work.

Staff meetings are held four times each week, at which unusual cases are submitted for study and diagnosis. During 1913 the accommodations in the Edgewood Building for 40 patients of the most disturbed class were finished and made ready for occupancy. Two considerable extensions of the reception building were finished, increasing the capacity of the building by 16. These additions were supplemented by spacious verandas. A large sewing room for the disturbed and semi-demented *omen patients was completed and an average of 70 patients are now employed therein.[1]

The Kirkbride[edit]

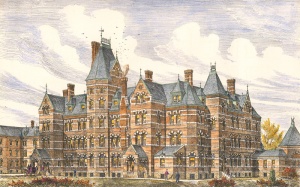

Frederick Clarke Withers designed the Kirkbride style Main Building in 1867. It was intended to be completed quickly, but went far over its original schedule and budget and remained under construction for almost a quarter century after it first opened. A nine-member Board of Managers was created and appointed to initiate and oversee construction of the actual building. Withers planned a building 1,500 feet (457 m) in length and over 500,000 square feet (45,000 m²) in area, most of its two wings that would house patients. It was the first institutional building in the U.S. designed in the High Victorian Gothic style. Calvert Vaux and Frederick Law Olmstead, designers of New York's Central Park, laid out the surrounding landscape. Like Withers, they had been mentored by the influential Andrew Jackson Downing in nearby Newburgh.

The centerpiece of his design was the administration building. The two wings, designed to hold 300 patients of either sex, were divided by a chapel placed between them in the yard behind the administration building so that patients could not see into the rooms of the opposite sex. The building and landscape plan were meant to aid in patients' recovery, by giving them adequate space and privacy and imbuing their healing with a sense of grandeur.

Construction began in 1868, with the cost estimated at $800,000. Cost-saving measures included the construction of a new dock on the Hudson so that building materials could be shipped more directly to the site, quarrying and cutting the foundation stones on site, mixing concrete from local materials and hiring local craftsmen instead of a general contractor. The board also deviated from the plan it had sent the state, in particular by building a shorter female wing when it came to believe that fewer patients of that sex would be admitted. As a result it is one of the few Kirkbride hospitals to have been built with asymmetrical wings.

Despite efforts to save money, the board was slightly over the $100,000 it had expected to spend that year, according to its first annual report. The main building was completed and opened, with 40 patients admitted, in October 1871. As work continued on other structures planned for the complex, so did the cost overruns. In 1873, the year county residents had been promised the hospital would be finished, the New York Times ran an editorial harshly criticizing the board for not only having gone way over budget but for lavish extravagance and waste:

The managers have entirely disregarded the law by which they were authorized to act. They have altered the plans and specifications ... Some of the details of the extravagance of the board are amazing. For instance, the first part of the work undertaken was the construction of a reservoir, into which the water was pumped from the river through an eight-inch (20 cm) iron pipe; from the reservoir the water was carried to the hospital by a twelve-inch (30 cm) iron pipe, the engine and machinery employed being on the scale of those used in supplying a neighboring city of 20,000 inhabitants. The cost of the reservoir was $100,000. Thirty thousand dollars was expended in blasting some rough rocks jutting into the reservoir, and the Superintendent gave as a reason for this that, if some of the patients were missing, they might want to rake the bottom of the reservoir to find the bodies, and with this the rocks would interfere ... The floors are laid in yellow Southern pine, the most expensive of the flooring, fitted and cut in a way greatly to enhance the cost. The heating is arranged on a scale that, with only 150 patients, ten tons (9 tonnes) of coal per day is consumed. The mention of these items sufficiently explains the disappearance of $1,200,000 of the people's money.

Some efforts were made to stop the project, but the legislature continued to appropriate funds despite further revelations like these. Construction continued until 1895, when further money could not be found. Despite this expenditure of time and money, the hospital's original plan was still not complete, and never would be.

Hudson River Psychiatric Center[edit]

Many new buildings continued to be constructed throughout the first part of the 20th century. As late as 1952 the institution was treating as many as 6,000 patients. Changes in the treatment of mental illness, such as psychotherapy and psychotropic drugs, were making large-scale facilities relics and allowing more patients to lead more normal lives without being committed. By the late 1970s the hospital administration decided to shut down the two main wings of the Kirkbride building, as few patients were residing in them and due to neglect some of the floors had collapsed. The state offices of Mental Health and Historic Preservation clashed over a plan to demolish the wings, even after the National Historic Landmark designation in 1989. In the 1990s, more and more of the hospital site would be abandoned as its services were needed less and less. The hospital consolidated with Harlem Valley Psychiatric Center in 1994 and closed the main campus (including the Kirkbride building) in 2001. The remaining hospital operations moved into a much smaller building nearby.

The state had decided to sell the main hospital campus for redevelopment, and in 2005 the Empire State Development Corporation sold 156 acres (62 ha) including the Kirkbride Main Building to Hudson Heritage LLC, a subsidiary of the Chazen Companies, for $2.75 million. Hudson Heritage and Chazen plan to thoroughly renovate the Kirkbride into a combination hotel/apartment complex as the centerpiece of a residential/commercial campus, Hudson Heritage Park. Redevelopment plans hit two setbacks later in the 2000s. In 2005, the Town of Poughkeepsie imposed a moratorium on new construction while it adjusted its zoning to deal with its growth. Hudson Heritage has been seeking to have a "historic revitalization district" created for the property that would help spur its growth. Then, on May 31, 2007, lightning struck the south wing of the Kirkbride, causing one of the most serious fires in Dutchess County's history. It is unclear whether that portion of the building can be effectively restored after such severe damage.[2] Starting in mid-2019, work has resumed on the Hudson Heritage project, with the treeline hiding the campus from NY Rt. 9 being removed, before demolition work on the campus buildings began in late 2019. After delays due to COVID-19 shutdowns, work has resumed [3].

Closure[edit]

In May 2011, New York Governor Andrew Cuomo announced a restructuring of mental health facilities after the Legislature adopted a budget that he said would close an overall state budget deficit of $10 billion. The closure of the Hudson River hospital would affect 375 workers and about 125 patients. A spokeswoman for the state Office of Mental Health, Leesa Rademacher, said most of the patients were moved over time after the announcement in 2011, the last 15 were relocated the week of the hospital's closing. Patients were moved to other New York facilities, primarily Rockland Psychiatric Center in Orangeburg. Many of the hospital employees took jobs in other facilities or state agencies where their civil service seniority gave them “bumping” rights to displace less-senior workers in similar titles. Others lost their jobs. The hospital was officially closed on January 25, 2011. [4]

Images of Hudson River State Hospital[edit]

Main Image Gallery: Hudson River State Hospital

Videos[edit]

- The following twenty-six-minute history of Hudson River State Hospital, created by The Cesspool YouTube channel, details the institution's long history.

- Video from Kirkbrides HD ~ http://www.vimeo.com/channels/KirkbridesHD

Links[edit]

- Hudson Heritage Park - The company that is redeveloping the hospital

- Harlem Valley.org - Lots of great postcards & information

- Historic 51 - A great site dedicated to the hospital

- Hudson River State Hospital @ Kirkbride Buildings

- Hudson River State Hospital @ Historic Asylums

References[edit]

- Jump up ↑ http://books.google.com/books?id=aPssAAAAYAAJ&pg=PA160&dq=editions:UOM39015005122398&client=firefox-a&output=text

- Jump up ↑ http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hudson_River_State_Hospital

- Jump up ↑ https://www.poughkeepsiejournal.com/story/news/local/2019/07/31/hudson-heritage-project-transform-hudson-river-psychiatric-center/1639202001/

- Jump up ↑ http://www.poughkeepsiejournal.com/article/20120125/NEWS01/301250015/Hudson-River-Psychiatric-Center-like-ghost-town-?odyssey=mod%7Cnewswell%7Ctext%7CPoughkeepsieJournal.com%7Cs

The Architecture of Madness-Insane Asylums in the United States, Yanni, Carla, University of Minnesota Press (2007)