Cook County Infirmary

| Cook County Infirmary | |

|---|---|

| |

| Established | 1869 |

| Opened | 1910 (Current Location) |

| Current Status | Active |

| Building Style | Pavilion Plan |

| Architect(s) | Holabird & Roche |

| Location | Oak Forest, IL |

| Alternate Names |

|

History[edit]

Under state law each county has had responsibility for providing a variety of social services to its most destitute residents, and in the nineteenth century each county in the Chicago region established its own almshouse. The Cook County Almshouse was the only public institution at any jurisdictional level specifically established to provide long-term refuge for the most extremely destitute people in the Chicago area. These were people with chronic physical illnesses or disabilities, mental illness or retardation, elderly people, or single mothers unable to work for a living even during periods when jobs were plentiful. Infamous for its corruption, mismanagement, deplorable living conditions, and maltreatment of inmates, the almshouse was regarded as a refuge of last resort. The number of residents ranged from 75 in 1854 to a peak of about 4,300 in January 1932, but usually the population, of whom approximately 10 percent were children, hovered around 1,000. The insane asylum department housed an additional 500–1,000 persons.

The Cook County commissioners allocated all almshouse funds and appointed the county agent, who not only determined admission to the almshouse but also distributed any county “outdoor” relief to “deserving” paupers. The commissioners also selected the staffs of the almshouse and the insane asylum. This situation erupted in major scandal nearly once every decade. In 1869, in an effort to make all public and private charitable institutions in Illinois more accountable, the legislature established a State Board of Public Charities. Its five members, private volunteers, were charged with visiting every institution in all 102 counties at least annually. Although they produced valuable biennial written reports and recommendations, they had no authority over the administration of the institutions.

Until the 1940s, almshouse personnel were largely untrained political appointees, but efforts were occasionally made to provide limited differential care. For example, because of concerns that the almshouse was an unfit environment for children, a schoolhouse and teacher were provided on the grounds. Separate cottages were allocated to lying-in patients and individuals with consumption or tuberculosis. More to prevent pandemonium than to provide special medical care, the county began maintaining an insane asylum in conjunction with the almshouse in 1870. When the almshouse moved from Dunning to Oak Forest, the insane asylum stayed behind to be turned over to state management. The Chicago State Hospital at Dunning, established in 1912, still exists.

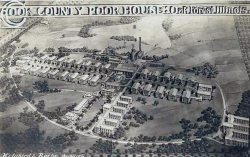

Although the county almshouse was originally located, from 1835 to 1841, in the center of Chicago on the town square (at Clark and Randolph), all subsequent locations were rural, chosen with the persistent if impractical idea that residents work the land to pay their way. These farms included 160 acres in Lake Township, 1841–1854; 160 acres five miles from the North Branch of the Chicago River, 1854–1883, expanded to 240 acres with new buildings and a county-constructed railroad station called Dunning, 1883–1910; and, finally, 360 acres in Bremen Township, the Oak Forest Infirmary designed by Holabird & Roche, 1911–1956. The farm ceased operation in 1956 when the institution became licensed as a hospital, but Oak Forest Hospital of Cook County remained on the site and continues to serve the chronically ill as part of the Cook County Health Care System.

Images[edit]

Main Image Gallery: Cook County Infirmary

Cemetery[edit]

St. Gabriel`s is the burial ground for 7,312 Catholics, most of whom were destitute or declared mentally ill and abandoned by their families to die in county homes early in the century. Despite the graves` lack of markers or gravestones, cemetery officials said they can pinpoint the plots of the people buried there since it was opened.