U.S. Narcotics Farm

| |

| Construction Began | 1933 |

|---|---|

| Opened | 1935 |

| Current Status | Active |

| Building Style | Rambling Plan |

| Peak Patient Population | 1,955 in 2000 |

| Alternate Names |

|

For nearly four decades, from the 1930s to the '70s, Lexington was a center for drug research and treatment. It drew addicts talented and desperate, obscure and celebrated, and provided free treatment and more: job training, sports, dental help, music lessons, even manicures. Research done there, much of it conducted with volunteer human subjects, yielded insights into drug addiction that still resonate today.

Jazz greats Chet Baker and Elvin Jones took the Lexington Cure. So did William S. Burroughs and his son, both of whom wrote about it. The father described the grueling detox but opined that the food was excellent. The son wrote about the place's isolation, and the joys of landing an easy job on-site.

A 1930s big government project emblematic of the New Deal, Narco was a joint venture of the Public Health Service and the Bureau of Prisons. The notion that thorny problems are best solved by a centralized bureaucracy is a concept that has seen happier days, but Narco's founders were sure that government, fueled by money and manpower, could change a nation's social landscape — from Lexington and a facility in Fort Worth Texas, that opened in 1938.

Lexington's countryside setting was important because this was a project that idealized rural life, built on a belief that if you turned up hopelessly addicted and worked in the sun, learned wholesome values, got dental care and played golf, maybe you could leave drugs behind. The nation, in the throes of the Depression, was flush with ambition if not cash, and drug addiction was seen as more of a bad habit than a brain-based physiological craving. But the odds of success with treatment at Narco were, it turned out, abysmally bad — as low as 7 percent, according to a 1962 survey.

"She rose proudly. She had spires and Roman cornices and Greek ramparts and punk American Depression symbols of electricity that coursed about the pregnant dirtybrown marble belly, and She pronounced the smug disunity of her period with disordered extensions and low, latched-on excrescences, and windows, windows, thousands & thousands of windows that hadn't been washed in decades, and stared like the cataract eyes of a square caterpillar onto the peacefully curving road that led into the black socket of her navel." — from The Farm by Clarence Cooper Jr., written in 1966

The Lexington Cure drew pop culture portrayals like a July picnic draws flies, but its depiction in the press changed over the decades, from unabashed heroic poses in the 1930s to the lurid tabloid coverage of the '50s. Photos from 1951 feature a patient undergoing withdrawal in the "shooting gallery," male patients lined up for a shot of morphine during detoxification. The caption on a photo of a barefoot teenage girl, face buried in her hands, reads: "Sweating it out after the withdrawal phase, a 17-year-old sits despondently on her bed, fighting the craving. Out of curiosity because others in her crowd took it, she smoked marijuana at 13 for a bang, then took heroin 'for a lift.'"

Heroin's popularity in the era's jazz circles, and the musicians' subsequent trips to Lexington, provided Narco with one of its greatest claims to fame: the Narco jazz band. But no audio of the band — including its 1964 performance on Johnny Carson's late-night television talk show — still exists. The band has a nickname: "the greatest band you never heard." The level of talent that passed through Narco was staggering: from jazz musicians to writers to those whose talents vanished beneath their unconquered addictions.

The Narco Farm was a prison, but it also offered free drug treatment to almost anyone who asked. Once on site, it was difficult to tell who was considered a criminal and who had simply lost their way to heroin — a drug once touted in the same ad with Bayer aspirin as a cure for coughs. All sorts of people checked in to Narco, but patient demographics shifted over the decades. When Narco first opened, its population skewed toward older, white addicts. But in the 1940s, more young addicts and African-Americans? were admitted. The Lexington Herald reported in 1955 that most Narco residents were addicted to heroin and the average patient was young and likely to be of African-American? or Latino descent.

Starting in 1968, those who qualified could serve six months of civil commitment for drug treatment instead of jail. Lexington became the toast of the civil commitment program.

But by 1972, the idea of a small treatment community that had evolved out of the behemoth Narco had become poisonous. The Lexington Herald reported in the early 1970s allegations that at Matrix House, one of the small communities, "some of the patients were stripped of their clothing and their pubic hair burned off, that some of the male patients' genitals were placed in ice water for long periods of time." Nude rituals and bomb-making were also alleged. By 1973, though, even the center's former boosters had turned against it. Dr. Harold Conrad, chief of the addiction research center at Narco, dismissed the place as being remote and no longer nationally unique.

In 1974, Narco was closed as a therapeutic center. On Dec. 31, 1976, the last human research subject there was transferred out. In 1984, its addiction research operations were moved to Baltimore. The prison became a Federal Correctional Institution, and then in 1991, changed its name to the Federal Medical Center. Hundreds of acres became Lexington's Masterson Station Park.

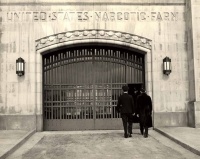

Now, 73 years after the complex opened, the drive up the hill is still as long as William Burroughs Jr. described it, and the architecture is still an exemplar of the United States governmental-behemoth style — a Biltmore built of good intentions. But it's now in the Lexington suburbs, not in the American countryside.

Even with cyclone fencing that lines the front façade, it still looks like a castle on the hill.

Images of U.S. Narcotics Farm

Main Image Gallery: U.S. Narcotics Farm