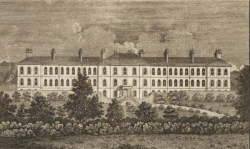

Sneinton Asylum

| Sneinton Asylum | |

|---|---|

| |

| Opened | 1811 |

| Closed | 1902 |

| Demolished | 1924 |

| Current Status | Demolished |

| Building Style | Single Building |

| Location | Nottingham |

| Alternate Names |

|

History[edit]

Two hundred years ago the General Lunatic Asylum of Nottingham opened its doors for the first time. The Borough Corporation attended in their regalia at the official opening on 11 October, 1811 but the first patients, six paupers from St. Mary’s parish, were not admitted until February 12th, 1812. It was the first County Asylum to open in England. George III’s mental illness in 1788 led to the problems of insanity being widely acknowledged. There were few asylums at that time, none in Nottinghamshire. Then in 1808 the Wynn Act was passed which allowed an asylum to be built in each county. Fund raising for an asylum had been going on for some years in Nottingham and now land in Sneinton was purchased. (The area is now King Edward Park on Carlton Road.) In January 1808 the Overseers of the Poor reported that there were 56 lunatics in the county. On that basis an asylum was built for 80, which was much too small and led to serious problems.

Dr. John Storer, physician to the General Hospital, was the leading figure in raising funds and getting the asylum built. Also very useful was the Rev. J. T. Becher of Southwell who had helped to design the workhouse there, and had much experience as a J.P. dealing with paupers. The design was the work of two men: Edward Staveley, the Nottingham Borough Surveyor, and the architect Richard Ingleman. They studied the methods used by the Quakers at the York retreat and at Brislington House, near Bristol.

The asylum cost over £20,000. The sum was raised by voluntary subscriptions (seven twelfths), the county rates (four twelfths) and the Nottingham town rates (one twelfth). In other words it was partly a charity. There were three classes of patients: 1. Private, paying 15/- (75p) per week; 2. Part paying; 3. Paupers, who were paid for by their parish at 9/- (45p) per week. Patients were supposed to be treated kindly, with little restraint and no corporal punishment, just as the Quakers did. However, there were occasional assaults and two patients were killed at Christmas 1814. Early on treatment consisted of emetics, purges, blood-letting and blistering. From 1827-30 the revolving chair was used, in which a patient was hurled round at 100 revs. per minute, resulting in vomiting, evacuation and even unconsciousness. The diet was a boring repetition of bread, meat, cheese, milk and beer, but it was much better than that in the workhouse. By the 1850’s some patients worked in the garden or laundry and got extra food. The asylum diet and cleanliness of the building prevented any major epidemics. The water supply and plumbing were very good by the standards of that day.

The Commissioners in Lunacy visited regularly and found it clean and quiet. However, four cells for noisy patients were built in 1815. Male and female patients were separated even in the airing yards. Physical restraint was never totally abolished; there were a few padded rooms, padded chairs and strait-jackets. There were many escapes in the early years, but by the end of the century the attendants were good at keeping the patients in and keeping them alive. There were no suicides between 1871 and 1886. The staff were above average for that time. Nurses and attendants had to clean and polish, make beds and meals, provide exercise, amusement, employment and supervision. They had to take temperatures, give enemas, apply poultices or a wet pack (cold wet sheets) for an over-excited patient. There were no night nurses until 1859. By mid-century many patients were doing jobs such as picking coir, knitting or cotton winding. Others were helping in the tailor’s shop or gardens, where they grew their own vegetables. There were some books and some games.

The constant problem of overcrowding led to demands for a new asylum. In 1855 the voluntary subscribers’ interest in Sneinton Asylum was purchased by Nottingham Borough and with the money a new asylum called The Coppice, designed by T. C. Hine, was built, which opened in August 1859. It was for first and second class patients only, and Sneinton was now for paupers only. Some of the reasons given for causes of insanity in 1858 were; intemperance (10 cases), epileptics (7), hereditary (19), religious excitement (1) and quarrel with a neighbour. In the 1860s others were certified insane who suffered from brain disease, delirium tremens, typhus and dementia. This led to even more overcrowding and in 1874 the Government decided to give parishes 4/- (20p) per head to move pauper lunatics from workhouses to asylums.

This resulted in even more pressure on beds in Nottingham Asylum. Thus a new asylum was needed and, in August 1880, Mapperley Hospital, designed by George Hine, T.C. Hine’s son, opened for pauper lunatics from the Borough of Nottingham only. Now the only patients at Sneinton were paupers from the county. There were so many empty beds that some patients were brought in from London in 1890 and from Hastings in 1891. However, this was only a temporary stop-gap and in spite of these other asylums the numbers being treated at Sneinton continued to rise. By 1900 there were 400 inmates. In the last quarter of the 19th century the building at Sneinton deteriorated badly. In 1891 the Commissioners in Lunacy condemned it as ‘this inconvenient, ill-constructed, ill-adapted asylum’. It was now under the control of the County Council who decided to press ahead with plans for a new asylum to replace Sneinton. From then on ‘this cheerless abode’ was allowed to run down. Yet, in 1900, the Superintendent, Dr. Alpin, claimed it cured ‘more than half of those who came to the asylum’. Not everybody who was mentally ill was confined to a Victorian asylum for many years.

The new asylum at Saxondale, near Radcliffe-on-Trent, was opened in July 1902. Nottingham Asylum at Sneinton then closed down, but for many years one wing of the building was used by the Dakeyne Street Boys’ Club. All that is left now is one pillar on Dakeyne Street.